| Kidney Res Clin Pract > Volume 35(2); 2016 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background

Successful pregnancy outcomes in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) are increasingly common in Western countries. However, in Korea, the available literature addressing this clinical issue is scarce.

Methods

We reviewed 5 successful parturitions [1 patient with Stage 5 CKD and 4 with maintenance hemodialysis (HD)] at Seoul St. Mary's Hospital over 3ô years and investigated changes in dialysis prescription, anemia management, and the incidence of maternal and neonatal complications.

Results

There were no maternal or neonatal deaths in this cohort. The mean age at the time of conception and delivery was 35.8ô ôÝô 3.7 and 36.2ô ôÝô 3.5 years, respectively. Dialysis patients received more frequent and intensified HD during pregnancy, 20.0ô ôÝô 5.7ô h/wk of HD over 5 visits with the ultrafiltration dose maintained between 1 and 2ô kg per session. All patients received erythropoietin-stimulating agents and iron replacement therapy during pregnancy. The mean hematocrit was 33.1ô ôÝô 1.9% before pregnancy and was well maintained during gestation (33.9ô ôÝô 3.8% at the first trimester, 29.2ô ôÝô 4.2% at the second trimester, and 33.6ô ôÝô 8.7% at delivery). The mean gestation period was 32.7ô ôÝô 4.7 weeks, with 60% of patients experiencing premature delivery. The primary maternal complication was pre-eclampsia; 3 women developed pre-eclampsia and underwent emergency cesarean sections. Most neonatal complications were related to preterm birth.

Conclusion

Dialysis-related care and general clinical management improved the clinical outcome of pregnancy for patients with advanced CKD.

Keywords

Chronic kidney disease, Dialysis, PregnancyPregnancy is a challenging prospect for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD). Indeed, women with CKD have an extremely low conception rate because of endocrine abnormalities and sexual dysfunction [1]. Even when fertilization is successful, the clinical outcome of pregnancy is unfavorable, with a greater frequency of spontaneous abortions and an increased risk of perinatal mortality.

Recent review articles reported improved pregnancy outcomes for patients with CKD [2], [3]. Furthermore, close attention to the management of anemia, blood pressure and volume control, as well as dialysis prescriptions seemed to contribute to these promising results. However, in Korea, the available literature addressing this clinical issue is scarce [4], [5], [6]. Managing this risky pregnancy complicated by CKD is unusual and can be a challenging experience for both the patient and her health care provider.

Herein, we report 5 cases of patients with advanced CKD who delivered in our medical center and had successful pregnancy outcomes. We hope that our findings will generate interest in this clinically complex issue.

We reviewed the records of women with advanced CKD who had successfully completed parturition at Seoul St. Mary's Hospital between January 2012 and December 2014. The study included patients who conceived when their glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was severely reduced (GFRô <ô 30ô mL/min) and who maintained their pregnancy beyond the first trimester.

We evaluated the incidence of maternal and neonatal deaths, pregnancy-related complications, changes in dialysis prescriptions, and anemia management during pregnancy. A total of 5 women were included in the study.

From the hospital computer records, we obtained clinical information, including maternal age at conception and delivery, parity, primary renal disease, other underlying medical conditions, dialysis prescriptions, dose of erythropoietin (EPO) and iron therapy, and maternal and fetal outcomes. We also collected biochemical and hematologicô data, including complete blood count, urea, creatinine, total protein, albumin, iron, total iron-binding capacity, and ferritin. Data are presented as the meanô ôÝô standard deviationô or counts and percentages to the nearest 10th.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital (KC15RISI0621).

Three of the 5 women were treated in local clinics before their referral to our center. The mean age at the time of conception and delivery was 35.8ô ôÝô 3.7 and 36.2ô ôÝô 3.5 years, respectively. The mean parity was 0.4, with 3 of the 5 patients having previously experienced spontaneous abortions. The primary causes of renal failure were rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (nô =ô 1), lupus nephritis (nô =ô 1), and immunoglobulin Aô nephropathy (nô =ô 1). Two cases were of unknown etiology (nô =ô 2). Four of the 5 pregnancies occurred while patients were on a regular hemodialysis (HD) regimen; the mean duration of HD before conception was 70.2ô ôÝô 35.2 months (Tableô 1). One predialysis patient had Stage 4 CKD at the time of conceptionô but developed Stage 5 CKD by the time of delivery. All patients had maintained good general health before conception, with mean serum albumin levels of 4.1ô ôÝô 0.4ô g/dL.

On average, pregnancy was detected at 12.2ô ôÝô 6.8 weeks gestational age (GA). After confirmation of pregnancy, 4 of the 5 patients commenced regular examinations at the obstetrics clinic in our center, with an average of 12.6 days between each visit. Fetal biometry, amniotic fluid index, and cervical length were measured at each appointment. Screening tests for aneuploidy were performed as scheduled, and the Doppler indices of placental and uterine blood flow were regularly monitored. A fetal nonstress test was performed at each visit in the third trimester or when the patient felt contractions. The fifth patient, who did not receive care at the obstetrics clinic in our center, underwent prenatal obstetric care at a local clinic with nephrology follow-up visits at our center during her pregnancy. She successfully delivered her newborn under the care of our multidisciplinary team that included specialists in nephrology, obstetrics, and neonatology. On average, the women gained 5.2ô ôÝô 2.6ô kg during pregnancy. One patient had a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, but the others underwent cesarean sections, including 3 emergency cesarean sections due to pre-eclampsia. Additional pregnancy-related maternal complications included 2 cases of polyhydramnios and 1 case of premature rupture of membranes before delivery. Moreover, 3 of the patients who received treatment for pre-eclampsia required additional treatment after delivery. One patient, who received intravenous magnesium sulfate for pre-eclampsia, developed hypermagnesemia with central nervous system manifestations, and 2 patients required additional treatment for pleural effusion and acute pulmonary edema (Tableô 2). During pregnancy, the sole predialysis patient experienced a gradual decrease in renal function, and HD was initiated a month after delivery.

Four dialysis patients received HD for an average of 70.2ô ôÝô 35.2 months before conception (Tableô 1). After the diagnosis of pregnancy, all dialysis patients received more frequent and intensified HD, which was on average 5 times/wk for a total of 20.0ô ôÝô 5.7ô hours. The ultrafiltration dose was essentially maintained in the range of 1ã2ô kg/session for all patients, and the mean interdialytic weight gain just before delivery was 2.1ô ôÝô 0.8ô kg (Tableô 3). The mean predialytic blood urea nitrogen level during gestation was less than 50ô mg/dL in all patients except Patient 1 (Patient 1, 66.2ô ôÝô 22.3; Patient 2, 34.9ô ôÝô 6.3; Patient 3, 44.3ô ôÝô 27.9; Patient 4, 40.7ô ôÝô 11.1; and Patient 5, 48.2ô ôÝô 11.0).

Three types of EPO-stimulating agents (ESAs) were used. Three patients received 165.8ô IU/kg/wk epoetin alfa at the beginning of their pregnancy and 161.2ô IU/kg/wk epoetin alfa at the end of their pregnancy. One patient received darbepoetin alfa at a dose of 2.0ô ö¥g/kg/moô at the beginning of her pregnancy and 3.7ô ö¥g/kg/moô at the end of the pregnancy. The last patient was predialytic and commenced treatment with methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta at a dose of 120ô ö¥g/moô at 18-weekô GA. Although the patient gained weight during pregnancy, her dose was not changed. All patients received iron replacement therapy around the second trimester. The mean dose of iron was 210.0ô mg/wk at the start of the second trimester and 184.0ô mg/wk at the month of delivery (Tableô 4).

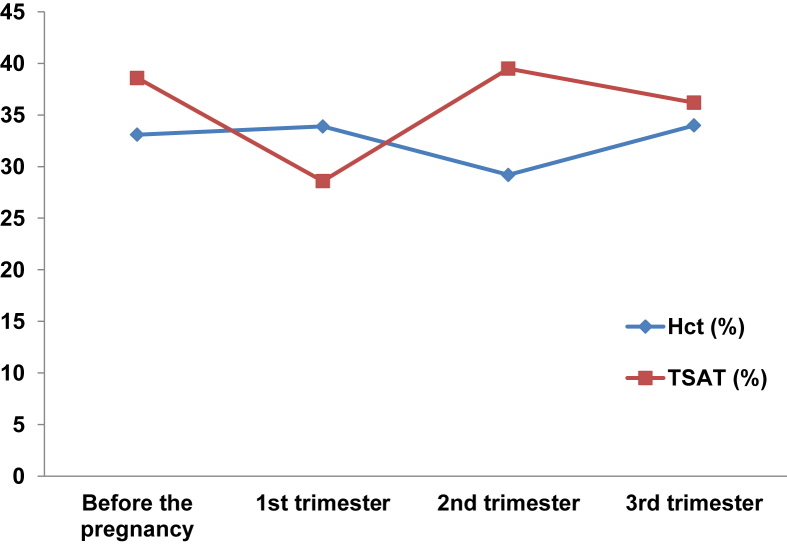

The respective mean levels of hemoglobin and hematocrit were 11.0ô ôÝô 1.0ô g/dL and 33.1ô ôÝô 1.9% before pregnancy, 10.9ô ôÝô 0.9ô g/dL and 33.9ô ôÝô 3.8% at the first trimester, 9.2ô ôÝô 1.2ô g/dL and 29.2ô ôÝô 4.2% at the second trimester, and 11.3ô ôÝô 1.7ô g/dL and 34.0ô ôÝô 4.9% at the third trimester, respectively. The mean transferrin saturation level was 38.6ô ôÝô 13.5% before pregnancy, 28.6ô ôÝô 1.1% at the first trimester, 39.5ô ôÝô 13.9% at the second trimester, and 36.2ô ôÝô 19.6% at the third trimester (Fig.ô 1). None of the patients required a transfusion during the course of pregnancy.

Four patients were treated with a single low-dose medication for chronic hypertension before pregnancy. Among 2 patients who had been initially prescribed monotherapy with 5ô mg of amlodipine, one later switched to an alternative calcium channel blocker, nifedipine (30ô mg), in the second trimester, and the other received combination therapy with add-on of atenolol (25ô mg/d) in the second trimester. One patient received antihypertensive management with carvedilol (12.5ô mg/d) throughout her pregnancy. One woman who was taking the angiotensin II receptor antagonist telmisartan, immediately terminated use of the medication when she discovered she was pregnant because of its known teratogenicity; she was prescribed 30ô mg/dô of nifedipine from 18-weekô gestation (Tableô 5). All patients maintained their blood pressure below 130/80ô mmHg throughout pregnancy, except the situation of pre-eclampsia.

The mean GA was 32.7ô ôÝô 4.7 weeks. Premature delivery occurred in 60% (3 of 5) of patients. Two full-term neonates had low birth weight (less than 2,500ô g), and 3 preterm neonates had very low birth weight (less than 1,500ô g). The mean birth weight of the newborns was 1,717.8ô ôÝô 633.4ô g (Tableô 6). Immediately after birth, newborns were transferred from the delivery room to receive individualized postnatal care by neonatologists. One healthy term newborn was transferred to the regular nursery, and the other 4 were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The full-term newborn who was transferred to the NICU received short-term ventilator assistance because of transient hypoxemia and was discharged on hospital Day 12. However, the preterm newborns developed intraventricular hemorrhage and respiratory distress syndrome with bronchopulmonary dysplasia despite surfactant administration. The postnatal course of these preterm neonates was also complicated by a large patent ductus arteriosus with heart failure, necrotizing enterocolitis, and neonatal sepsis. The average length of stay in the NICU for the preterm neonates was 131.0ô ôÝô 94.5 days (Tableô 6). Except for one newborn who was transferred to another tertiary hospital at 240 days of age, all newborns were eventually discharged in good health.

Although recent case series and systematic reviews have reported a trend toward improved pregnancy outcomes for patients with advanced CKD, in Korea, the pregnancy outcomes in these high-risk patients remainô under-reported. Here, we present recent successful pregnancies in women with advanced CKD in the Seoul St. Mary's Hospital dialysis center.

Despite the small possibility of conception and maintenance of pregnancy faced by patients with CKD, in our center, 7 women with CKD successfully delivered newborns. Five of these patients had a GFR less than 15 mL/min/1.73ô m2 and were included in our study. Four of these patients were treated with HD for an average duration of 70.2ô ôÝô 35.2 months before conceptionãa far lengthier preconception period of dialysis than reported by other studies [7], [8]. It was encouraging that these pregnancies in patients with advanced CKD resulted in 5 successful deliveries over a 3-year period at a single center.

Most likely, several factors contributed to these positive results. First, all our patients were in a good general health at the time of conception. For example, the average level of serum albumin, which was measured serially during prenatal care, was 4.1ô ôÝô 0.4ô g/dL before pregnancy and was maintained above 3.0ô g/dL by all patients throughout pregnancy. Because albumin is considered to be representative of a patient's nutritional and inflammatory status, we can assume that these women were able to achieve optimal dietary intake and an inflammation-free status before and during gestation. This most likely contributed to the successful occurrence and maintenance of their pregnancies.

Well-controlled blood pressure could be another contributing factor to successful conception and maintenance of pregnancy. Most patients with CKD have chronic hypertension and tend to require multidrug treatment. Moreover, patients who require multiple medications for blood pressure control or those whose hypertension is poorly controlled are at an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including maternal morbidity and fetal loss [9]. However, among our patients, one was normotensive and the others maintained their blood pressure under control with single, low-dose antihypertensive therapy. Before the development of pre-eclampsia, blood pressure was maintained below 130/80ô mmHg for all patients during pregnancy. This maintenance of the maternal blood pressure may have helped to stabilize the fetoplacental circulation.

Technological improvements in dialysis and more intensive dialysis are also crucial contributors to these positive outcomes. To avoid excessive fluid loss and sudden changes in osmolarity, pregnant patients are recommended a high biocompatibility dialyzer with a lower surface area and increased time on dialysis [2], [3], [7], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. Frequent dialysis during pregnancy may allow for better and gentler fluid and blood pressure management, liberal fluid and diet intake, and greater reductions in the level of urea [10]. In the present study, all 4 dialysis patients were treated with a high biocompatible dialyzer with a surface area of less than 1.5ô m2. Moreover, they received regular HD that was increased after pregnancy confirmation (from 11.0ô ôÝô 2.0ô h/wk to 20.0ô ôÝô 5.7ô h/wk), and the ultrafiltration dose was maintained at less than 2.0ô kg/session. Although several review articles have suggested that increasing the frequency of HD after the second trimester to more than 5ô sessions/wk might lead to better fetal outcomes, 1 patient in our center received only 3 sessions of HD/wk until delivery. Two years previously, she got sudden damage to kidney due to pre-eclampsia and increase in lupus activity during her first delivery. Although she was undergoing less frequent HD, her daily urine output was maintained at approximately 1,000ô mL, which was sufficient to achieve a healthy status without significant volume overload, uremia, or electrolyte imbalance. During her second pregnancy 2ô years later, we adjusted her HD frequency from semiweekly to 3 times a week and monitored her volume and biochemical status. This HD schedule was well tolerated and was maintained during the entire gestation. Ultimately, she delivered a healthy, term newborn. These findings suggest that, in pregnant patients with end-stage renal disease, the level to which the frequency of dialysis is increased should be individualized.

We used a well-accepted approach toward the management of anemia. During a healthy pregnancy, erythrocyte volume increases by an average of 450ô mL, and vigorous erythropoiesis leads to a large requirement for iron. In uncomplicated pregnancies, iron supplementation of just 6ã7ô mg/dô is sufficient to satisfy this requirement [9]. However, because they are often deficient in EPO, pregnant women with advanced CKD require supplementation with both iron and EPO to maintain acceptable hematologic parameters. Pregnant women with CKD who are anemic have a higher risk of preterm labor [2], [16]. The use of high-dose EPO in combination with iron therapy has also been shown to eliminate the need for blood transfusions in such patients [2], [7], [17], [18], [19]. In this study, 3 patients received an ESA at a higher dosage. The only predialytic patient began treatment with an ESA midtrimester. Although 1 patient received rather lower dosage of EPO during pregnancy, hematologic parameters were closely monitored in all patients, and the hemoglobin and hematocrit levels were largely maintained over 10.0ô g/dL and 30%, respectively. No patient required a blood transfusion at any time during her pregnancy.

Finally, a multidisciplinary team approach that includes nephrologists, obstetricians, and neonatologists is likely to have a positive influence on pregnancy outcomes for women with CKD. Our active management of dialysis and anemia treatment was combined with frequent antenatal obstetric follow-up. In addition, newborns received immediate, intensive postnatal care. Pertinent patient information was shared among team members in advance, enabling the proper handling of adverse events, even in emergency situations. Although the majority of neonates were born prematurely, all were discharged from the hospital alive.

Nevertheless, similar to previous studies, there were several adverse outcomes. Renal dysfunction is known to increase the risk of pre-eclampsia. In one of the largest case series to date that included 52 pregnancies, Luders etô al [20]ô reported that pre-eclampsia was diagnosed in 10 (19.2%) patients and negatively affected the rate of successful deliveries. In our study, apart from 1 patient who had a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, all patients had cesarean sections, with 3 women undergoing emergency operations due to pre-eclampsia. Although the patients delivered in a timely fashion before the development of eclampsia, one patient experienced hypermagnesemia-induced diplopia and vomiting during magnesium sulfate therapy for pre-eclampsia. In patients with advanced CKD who have difficulty regulating electrolyte balance, meticulous care is required when administering with intravenous magnesium for the management of pre-eclampsia.

The failure to achieve optimal pregnancy weight gain during pregnancy likely contributed to intrauterine growth restriction. Pregnant women are encouraged to gain at least 11ã12ô kg (0.36ã0.45ô kg/wk) [9], and dialysis patients require a weight gain of approximately 0.5ô kg/wk to avoid maternal hypotension and volume depletion [10], [18]. The patients in our study, however, gained an average of just 5.2ô kg, which is lower than recommended and may explain why their babies were small for their GA. Based on the recommendations outlined in textbooks and review articles, a weight gain of 0.36ã0.5ô kg/wk may help to prevent preterm birth and fetal-growth restriction. In pregnant patients with advanced CKD, it is difficult to determine how much of the weight gain is because of excess fluid rather than pregnancy-associated weight gain. Nevertheless, these patients should be encouraged to achieve an optimal pregnancy weight gain with careful weekly examinations to look for signs of fluid overload.

Consistent with other studies, the incidence of suboptimal fetal outcomes remained high in women with advanced CKD, notwithstanding advances in obstetrical and neonatal care [21]. In our investigation, all 5 newborns were small for their GA and 3 of them experienced various complications related to preterm delivery. Four newborns were admitted to the NICU, for an average of 81 days, and one of them was transferred to the neonatal care unit at another center on hospital Day 240. Although there was no neonatal death during hospitalization in our medical center, we do not have follow-up information about the newborn who was transferred to another medical center. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility of an infant death.

Our study has several limitations. First, this is an observational study, and the number of patients included is too small to establish a causal relationship between kidney disease and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Second, we did not have objective data to evaluate the adequacy of dialysisô or a body water-indexed clearanceô ûô time product (Kt/V). Nevertheless, this study is meaningful because it is the first report in Korea that includes 5 consecutive cases of pregnant patients with advanced CKD who achieved a successful pregnancy outcome. We hope that our experience will generate interest in these high-risk pregnancies and help to guide clinical management of similar patients.

In summary, our article describes successful pregnancy outcomes in 5 women with advanced CKD. Clearly, the small number of patients necessitates a larger scale observational study. Nevertheless, we cautiously conclude that these encouraging outcomes resulted from the maintenance of good general health before conception and intensive multidisciplinary management after pregnancy confirmation. The rate ofô neonatal complications is still high and remains to be addressed. We hope that our report will be helpful to health care providers in counseling and managing women with advanced CKD during pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea (HI14C3417).

References

1. Nadeau-Fredette A.C., Hladunewich M., Hui D., Keunen J., Chan C.T.. End-stage renal disease and pregnancy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 20:2013;246ã252.

2. Manisco G., Poti M., Maggiulli G., Di Tullio M., Losappio V., Vernaglione L.. Pregnancy in end-stage renal disease patients on dialysis: how to achieve a successful delivery. Clin Kidney J 8:2015;293ã299.

3. Alkhunaizi A., Melamed N., Hladunewich M.A.. Pregnancy in advanced chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 24:2015;252ã259.

4. Jung J.H., Kim M.J., Lim H.J., Sung S.A., Lee S.Y., Kim D.W., Lee K.B., Hwang Y.H.. Successful pregnancy in a patient with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease on long-term hemodialysis. Jô Korean Med Sci 29:2014;301ã304.

5. Sohn S.W., Lee D.Y., Ahn S.Y., Chung I.B., Cha D.S., Kim D.H.. Two cases of successful pregnancy outcome with hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patient. Korean J Perinatol 4:1993;408ã414.

6. Rhee S.K., Kim S.S., Jeong M.S., Lee K.W., Shin Y.T., Nam S.L., Byun S.H.. Aô case of successful pregnancy and birth in chronic renal failure patient receiving hemodialysis. Korean J Nephrol 12:1993;476ã480.

7. Haase M., Morgera S., Bamberg C., Halle H., Martini S., Hocher B., Diekmann F., Dragun D., Peters H., Neumayer H.H., Budde K.. Aô systematic approach to managing pregnant dialysis patientsãthe importance of an intensified haemodiafiltration protocol. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20:2005;2537ã2542.

8. Barua M., Hladunewich M., Keunen J., Pierratos A., McFarlane P., Sood M., Chan C.T.. Successful pregnancies on nocturnal home hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3:2008;392ã396.

9. Cunningham F.G., Leveno K.J., Bloom S.L., Spong C.Y., Dashe J.S., Hoffman B.L., Casey B.M., Sheffield J.S.. Williams Obstetrics. 24th edition. 2014. McGraw-Hill Education; New York: p. 51ã56.

10. Reddy S.S., Holley J.L.. Management of the pregnant chronic dialysis patient. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14:2007;146ã155.

11. Hladunewich M.A., Hou S., Odutayo A., Cornelis T., Pierratos A., Goldstein M., Tennankore K., Keunen J., Hui D., Chan C.T.. Intensive hemodialysis associates with improved pregnancy outcomes: a Canadian and United States cohort comparison. Jô Am Soc Nephrol 25:2014;1103ã1109.

12. Bagon J.A., Vernaeve H., De Muylder X., Lafontaine J.J., Martens J., Van Roost G.. Pregnancy and dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 31:1998;756ã765.

13. Okundaye I., Abrinko P., Hou S.. Registry of pregnancy in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 31:1998;766ã773.

14. Villa G., Montagna G., Segagni S.. Pregnancy in chronic dialysis. A case report and a review of the literature. Gô Ital Nefrol 24:2007;132ã140.

15. Gangji A.S., Windrim R., Gandhi S., Silverman J.A., Chan C.T.. Successful pregnancy with nocturnal hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 44:2004;912ã916.

16. Levy A., Fraser D., Katz M., Mazor M., Sheiner E.. Maternal anemia during pregnancy is an independent risk factor for low birthweight and preterm delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 122:2005;182ã186.

17. Asamiya Y., Otsubo S., Matsuda Y., Kimata N., Kikuchi K., Miwa N., Uchida K., Mineshima M., Mitani M., Ohta H., Nitta K., Akiba T.. The importance of low blood urea nitrogen levels in pregnant patients undergoing hemodialysis to optimize birth weight and gestational age. Kidney Int 75:2009;1217ã1222.

18. Holley J.L., Reddy S.S.. Pregnancy in dialysis patients: a review of outcomes, complications, and management. Semin Dial 16:2003;384ã388.

19. Vazquez-Rodriguez J.G.. Hemodialysis and pregnancy: technical aspects. Cir Cir 78:2010;99ã102.

Figureô 1

Average of serum hematocrit level and transferrin saturation at each pregnancy period.

Hct, hematocrit; TSAT, transferrin saturation.

Tableô 1

Characteristics of patients

| Patient | Age (y)ã | Primary renal disease | Obstetric historyã | Time on dialysis (mo)ãÀ | Urination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 38/38 | RPGN | 1-0-0-1 | 60.5 | No |

| 2 | 40/40 | Unknown | 0-0-0-0 | 99.6 | No |

| 3 | 32/33 | Unknown | 0-0-2-0 | 96.1 | No |

| 4 | 37/38 | Lupus nephritis | 1-0-1-1 | 24.5 | Yes |

| 5 | 31/32 | IgA nephropathy | 0-0-1-0 | ã | Yes |

Tableô 2

Characteristics of pregnancies

| Patient | Pregnancy detection | Body weight (kg)ã | Mode of delivery |

Complications |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before delivery | After delivery | ||||

| 1 | 20 GA | 57.8/59.7 | NSD | ã | ã |

| 2 | 12 GA | 50.0/53.5 | C-sec | PE, PROM | ã |

| 3 | 6 GA | 50.0/57.8 | C-sec | PE, polyhydramnios, cervix insufficiency | Pulmonary edema, pleural effusion |

| 4 | 18 GA | 59.5/64.9 | C-sec | ã | ã |

| 5 | 5 GA | 41.7/49.3 | C-sec | PE, polyhydramnios, CKD progression | Pulmonary edema, pleural effusion, hypermagnesemia |

Tableô 3

Characteristics of dialysis

| Patient | RRT modality | Dialyzer | HD frequency (/wk)ã | HD duration (h/wk)ã | Interdialytic weight gain (kg)ã |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HD | REXBRANE (Asahi Polysulfone); 1.5 m2 | 3/5 | 12/20 | 2 |

| 2 | HD | Polyamixô (polyarylethersulfone, polyvinylpyrrolidone, polyamide); 1.4 m2 | 3/6 | 12/24 | 1.1 |

| 3 | HD | Polyamixô (polyarylethersulfone, polyvinylpyrrolidone, polyamide); 1.4 m2 | 3/6 | 12/24 | 3 |

| 4 | HD | Polyamixô (polyarylethersulfone, polyvinylpyrrolidone, polyamide); 1.3 m2 | 2/3 | 8/12 | 2.2 |

Tableô 4

Anemia management

| Patient | ESA therapyã | Iron supplementationã | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Epoetin alfa | 17.3/201.0ãÀ | 140.0/140.0/140.0 |

| 2 | Epoetin alfa | 240.0/74.8ãÀ | 0/50.0/50.0 |

| 3 | Epoetin alfa | 240.0/207.8ãÀ | 0/270.0/270.0 |

| 4 | Darbepoetin alfa | 2.0/3.7ôÏ | 0/320.0/190.0 |

| 5 | Methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin öý | 2.9/2.4ôÏ | 0/270.0/270.0 |

Tableô 5

Blood pressure management

Tableô 6

Characteristics of neonates

| Patient | GA at birth | Birth weight (g) | Apgar scoresã | Complications | NICU admission (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37 + 5 | 2,460 | 8/9 | LBW | 0 |

| 2 | 29 + 3 | 1,252 | 1/4 | Prematurity, VLBW, RDS, BPD, PDA, IVH, PH | 240 |

| 3 | 27 + 3 | 1,090 | 4/8 | Prematurity, VLBW, RDS, BPD, IVH, NEC | 73 |

| 4 | 37 + 3 | 2,330 | 8/9 | LBW | 12 |

| 5 | 31 + 2 | 1,457 | 6/8 | Prematurity, VLBW, RDS, BPD, IVH, neonatal sepsis | 80 |

BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; GA, gestational age; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; LBW, low birth weight; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PH, pulmonary hypertension; RDS, respiratory distress syndrome; VLBW, very low birth weight.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles

-

Nephrology consultation improves the clinical outcomes of patients with acute kidney injury

Skeletal muscle energetics in patients with moderate to advanced kidney disease2022 January;41(1)

The roles of sodium and volume overload on hypertension in chronic kidney disease2021 December;40(4)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print