Incidence of acute cholecystitis underwent cholecystectomy in incident dialysis patients: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background

Patients on dialysis have numerous gastrointestinal problems related to uremia, which may represent concealed cholecystitis. We investigated the incidence and risk of acute cholecystitis in dialysis patients and used national health insurance data to identify acute cholecystitis in Korea.

Methods

The Korean National Health Insurance Database was used, with excerpted data from the insurance claim of the International Classification of Diseases code of dialysis and acute cholecystitis treated with cholecystectomy. We included all patients who commenced dialysis between 2004 and 2013 and selected the same number of controls via propensity score matching.

Results

A total of 59,999 dialysis and control patients were analyzed; of these, 3,940 dialysis patients (6.6%) and 647 controls (1.1%) developed acute cholecystitis. The overall incidence of acute cholecystitis was 8.04-fold higher in dialysis patients than in controls (95% confidence interval, 7.40–8.76). The acute cholecystitis incidence rate (incidence rate ratio, 23.13) was especially high in the oldest group of dialysis patients (aged ≥80 years) compared with that of controls. Dialysis was a significant risk factor for acute cholecystitis (adjusted hazard ratio, 8.94; 95% confidence interval, 8.19–9.76). Acute cholecystitis developed in 3,558 of 54,103 hemodialysis patients (6.6%) and in 382 of 5,896 patients (6.5%) undergoing peritoneal dialysis.

Conclusions

Patients undergoing dialysis had a higher incidence and risk of acute cholecystitis than the general population. The possibility of a gallbladder disorder developing in patients with gastrointestinal problems should be considered in the dialysis clinic.

Introduction

Acute cholecystitis, an inflammatory gallbladder disorder usually caused by gallstones, is a common gastrointestinal disease in Korea. Despite a good prognosis, it can lead to high morbidity and mortality without proper diagnosis and treatment. The most common symptom is upper abdominal pain, which usually begins in the epigastric region and is then localized to the right upper quadrant. Nausea, vomiting, and fever are generally significant [1]. The prevalence of acute cholecystitis among individuals with abdominal pain is 3% to 8%, and its incidence is markedly increased after the age of 50 years in the general population [2]. The 30-day mortality was 1.1% in a Japanese-Taiwanese study with similar ethnic characteristics as that of the Korean population [3].

As life expectancy increases, the number of patients with diabetes and hypertension increases globally. The increased number of chronic kidney disease cases correspondingly increases the dialysis population [4], and improved cardiovascular outcomes in the dialysis population result in prolonged dialysis duration and enhanced long-term survival [5]. However, elderly patients demonstrated a relatively decreased survival gain because of multiple medical problems [6]. Therefore, general medical care with superior quality has become important for dialysis patients.

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) have multiple problems associated with uremia. They have more common nonspecific gastrointestinal problems such as abdominal pain, constipation, dyspepsia, nausea, and irritable bowel syndrome than controls without renal impairment [7]. Although uremia is thought to cause nonspecific gastrointestinal problems, it could mimic specific gastrointestinal illnesses that could result in the misdiagnosis of an important disease. Furthermore, dialysis patients have a higher incidence of gastrointestinal disease than the general population [8]. However, the incidence of acute cholecystitis, its clinical characteristics, and treatment outcomes in dialysis patients are still not fully understood.

This study aimed to determine the incidence and risk of acute cholecystitis in the dialysis population and to investigate the differences among the dialysis modalities in patients with ESRD. We designed a propensity score-matched cohort study using the Korean National Health Insurance Service (KNHIS) data.

Methods

Database

Data on patients undergoing dialysis were obtained from the Korean National Health Information database. The KNHIS, a single national insurance provider, covers almost the entire Korean population. This database, which contains reimbursement records from all medical facilities across the country, was used to develop an exposure cohort. We previously reported the incidence of active tuberculosis and cancer in dialysis patients using KNHIS data [9,10].

Definition and selection of cohort

All incidental patients with ESRD who underwent dialysis for more than 3 months and were diagnosed between 2004 and 2013 in Korea were selected from the database to establish the exposure cohort. The dialysis cohort included patients who claimed insurance for any procedures or services for both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, based on the Korean electronic data interchange codes (O7020, O7021, O9991 for hemodialysis; E6593, O7061, O7062, O7074, O7075, O7080 for peritoneal dialysis) combined with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code of chronic kidney disease (N18.**) [10]. Patients who underwent dialysis for more than 3 months were defined by a dialysis code that appeared again within 3 months after the initial dialysis code appeared. In the peritoneal dialysis patient group, codes (O7061 and O7062) were used to find new patients receiving peritoneal dialysis. The date these codes appeared was the first peritoneal dialysis date, and the cases where the peritoneal dialysis code reappeared after 3 months was the peritoneal dialysis patient group.

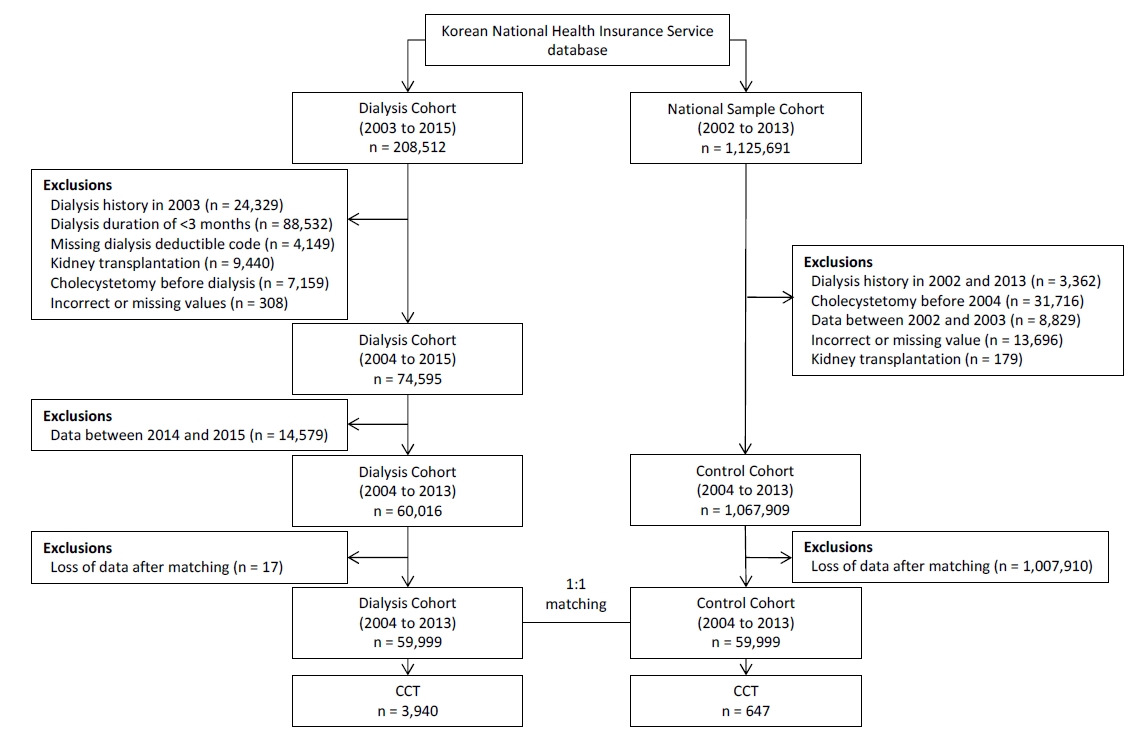

Patients with a diagnosis of ESRD who were provided with medical services in 2003 and received kidney transplantation were excluded from this cohort to rule out chronic ESRD (Fig. 1).

Patient and control enrollment flowchart showing the selection from the database.

We evaluated 59,999 patients and compared them with 59,999 non-dialysis subjects selected from the National Sample Cohort of 1,125,691 Koreans via propensity score matching.

CCT, acute cholecystitis patients who underwent cholecystectomy.

The control cohort was selected from the KNHIS National Sample Cohort (NSC) from the National Health Information database established by the KNHIS in 2011 [11]. These cohort data covered 1,125,691 Korean individuals and represented 2.2% of all Korean population disease entities. We excluded patients with dialysis, diagnosed with cholecystitis and/or cholecystectomy, or kidney transplantation (Fig. 1).

Definition of acute cholecystitis and covariables

The incidence of acute cholecystitis was investigated using ICD 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes. Acute cholecystitis was defined as follows; admission to an acute care hospital with diagnostic codes of acute or other cholecystitis regardless of calculus (ICD-10 K80, K81, K82) with confirmed cholecystitis by pathology after performing cholecystectomy (Q7380) [12]. We excluded patients who were diagnosed with cholecystitis and/or cholecystectomy before the start of dialysis. The factors associated with the incidence of acute cholecystitis, such as age, sex, income level, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), and comorbidities, were used as independent variables. The comorbidities for covariates, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, connective tissue disease, myocardial infarction, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, severe liver disease, dementia, and atrial fibrillation, were selected based on a previous Taiwanese nationwide study [13,14] (Supplementary Material, available online). Income level was categorized into three groups after it was scored on a scale of 0 to 10.

Propensity score matching

We included patients who began dialysis before their diagnosis of acute cholecystitis based on the visit date. Dialysis cohort data between 2014 and 2015 were excluded because in the KNHIS-NSC database only data up to 2013 was available. The eligible patients, who started dialysis between 2004 and 2013 (dialysis cohort), were identified after excluding potentially preexisting cases of dialysis or acute cholecystitis. We identified individuals without ESRD from the KNHIS-NSC database, who were propensity score-matched to an equal number of ESRD cases. Propensity score matching using the nearest neighbor method was performed to identify similar individuals in the dialysis and control cohorts [15]. Logistic regression was used to obtain propensity scores for each patient based on their age, sex, income level, and CCI as well as comorbidities. Individuals in both cohorts were randomly ordered and matched 1:1 using the nearest neighbor method (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis

Proportional differences in independent variables between the dialysis and control cohorts were analyzed using the Wald chi-square test. The acute cholecystitis incidence rate was expressed as the number of newly diagnosed acute cholecystitis cases per 10,000 person-years from the database. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) of dialysis cohorts, relative to the controls, was calculated with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The cumulative incidence of acute cholecystitis was calculated by using the Kaplan-Meier method and analyzed by the log-rank test. We applied the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to all independent variables after combining the two cohorts to determine the dialysis-associated risk of developing acute cholecystitis, which was described as hazard ratio (HR). The follow-up period started on the first date of dialysis for the cases and on randomly selected visit dates for the controls, which occurred in years that matched the start of dialysis for the cases. The follow-up period ended on the first date of acute cholecystitis diagnosis or the last follow-up date. Analyses were performed using the statistical package SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R version 3.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A statistical significance level of 0.05 was established.

Ethics statement

The retrospective protocol of this study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Chungbuk National University Hospital in Cheongju, Republic of Korea (No. 2016-11-009). We used encrypted national insurance data. The IRB exempted our study from informed consent. All encrypted patients’ records from the KNHIS were anonymized to ensure patient confidentiality.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the dialysis and control cohort

A total of 208,512 patients who were newly diagnosed with ESRD were selected from the KNHIS database. Patients who had undergone dialysis before 2003 (24,329), with a dialysis duration of less than 3 months (88,532), without a dialysis deductible code (4,149), who had incorrect or missing value (308), and who had kidney transplantation (9,440) were excluded. Patients who underwent cholecystectomy before the initiation of dialysis (7,159) were also excluded. A total of 59,999 patients were included in the patient arm, and 59,999 patients from the NSC of the 1,125,691 Korean population were included in the propensity score-matched group (Fig. 1).

The baseline characteristics and comorbidities between the dialysis and control cohorts are summarized in Table 1. In the dialysis cohort, 34,772 patients (58.0%) were men, and the mean duration of dialysis was 2.76 ± 2.76 years. The dialysis patients commonly commenced at 50 to 79 years of age (43,346, 72.0%) in comparison with a similar number of patients in the matched control cohort. In total, 54,103 patients underwent hemodialysis (90.2%), whereas 5,896 underwent peritoneal dialysis (9.8%).

Comparison of acute cholecystitis in the dialysis and control cohort

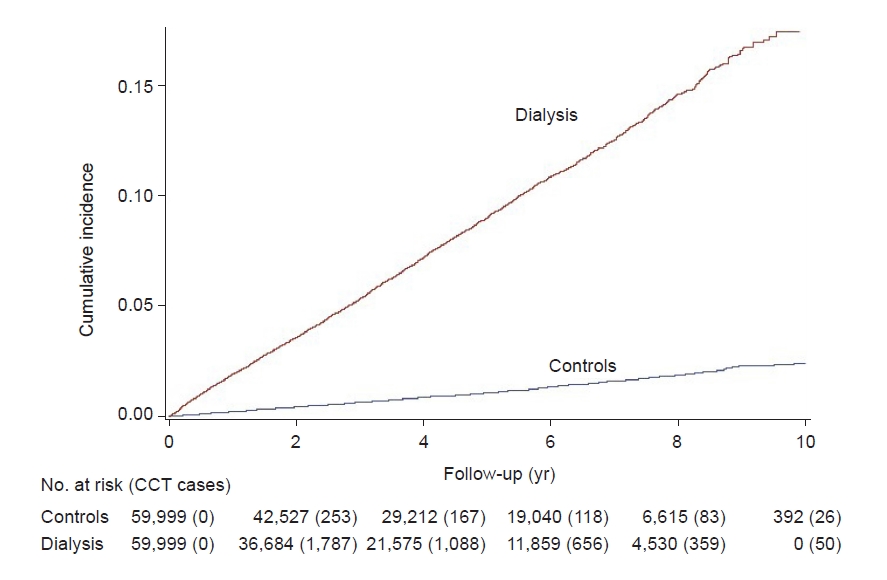

Among the 59,999 dialysis patients and 59,999 controls, 3,940 dialysis patients (6.6%) developed acute cholecystitis, and 647 controls (1.1%) developed cholecystitis (Table 2). The overall incidence of acute cholecystitis was remarkably higher in the dialysis patients than controls (IRR, 8.04; 95% CI, 7.40–8.76). The cumulative incidence of acute cholecystitis was significantly higher in dialysis patients than controls (p < 0.001), the result is illustrated in Fig. 2. In the subgroup analysis, the incidence of acute cholecystitis was similarly elevated in the dialysis group (Table 2). Because the variables were different between dialysis and the control group, we analyzed the HR by multivariate analysis. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis revealed that dialysis was a significant risk factor for acute cholecystitis with an HR of 8.94 (95% CI, 8.19–9.76) (Table 3).

The incidence of acute cholecystitis according to baseline characteristics among dialysis patients and controls

Cumulative incidence of acute cholecystitis in patients with end-stage renal disease and controls.

The cumulative incidence of acute cholecystitis was significantly higher in dialysis patients (p < 0.001).

CCT, acute cholecystitis patients who underwent cholecystectomy.

In the subgroup of dialysis modality, acute cholecystitis occurred in 3,558 of 54,103 hemodialysis patients (6.6%) and in 382 of 5,896 peritoneal dialysis patients (6.5%). After variables were adjusted, hemodialysis patients were at a lower risk of acute cholecystitis than peritoneal dialysis patients (adjusted HRs, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.76–0.94; p < 0.01), and a significant difference was observed (Table 4, Fig. 3).

Discussion

This nationwide cohort study found that patients with ESRD undergoing dialysis were associated with an 8.94-fold higher risk of acute cholecystitis than the matched control group. This is the largest cohort study to investigate the incidence and risk factors of acute cholecystitis after the initiation of dialysis for ESRD in the Korean population. A recent Taiwanese nationwide cohort study that consisted of 54,065 patients with new-onset ESRD reported that the incidence of acute cholecystitis was 5.8/1,000 patient-years. In addition, patients with ESRD were associated with a 6.83-fold higher risk of developing acute cholecystitis [13].

Acute cholecystitis is commonly associated with inflammation caused by prolonged obstruction of the cystic duct with gallstones [16]. Even though gallstones are the most important factor in the pathogenesis of acute cholecystitis, there are also many other investigated factors for developing gallstones [17,18]. Although many studies have investigated the relationship between gallstones and ESRD, it remains to be clarified whether gallstones are more common in patients with ESRD [16–18]. Some studies report that the incidence of gallstones in patients on hemodialysis was not different from that in controls [19–24], whereas others have reported a higher incidence of gallstones in patients on hemodialysis than in the control group [25–30]. In this study, both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis were associated with an increased risk of developing acute cholecystitis. In terms of dialysis modality, hemodialysis patients were at a lower risk of acute cholecystitis than peritoneal dialysis patients.

In patients on hemodialysis, hemodynamic fluctuations cause hypoperfusion to organs. The resulting frequent mesenteric ischemia leads to disruption of the gut mucosal structure with increased gut permeability, and chronic malnutrition causing a higher incidence of peptic ulcer disease. Dialysis patients with poor nutrition have a higher incidence of peptic ulcer disease [31]. This could occur in the gallbladder. The ischemia and reperfusion injury leads to epithelial damage of the gallbladder. Additionally, increased circulating uremic toxin levels in hemodialysis patients cause systemic inflammation. Moreover, increased leukocyte margination and focal lymphatic dilation with interstitial edema are associated with local microvascular occlusion [32–34]. In peritoneal dialysis patients, acute cholecystitis is caused by chronic active inflammation of the peritoneum and endotoxemia [35,36]. We hypothesize that chronic inflammation of the gallbladder and decreased gallbladder motility due to uremia caused the increased incidence of cholecystitis.

In the management of acute cholecystitis, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is recommended as a first-line treatment in the general population [37]. However, previous studies on the outcomes of patients with ESRD undergoing cholecystectomy have reported that ESRD is an independent risk factor for postoperative morbidity [38,39]. Although patients on dialysis are at risk of postoperative complications, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is recommended as a first-line treatment for acute cholecystitis even in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis [40–44]. In severe acute cholecystitis, operative management increased morbidity and mortality. Chung et al. [45] reported that emergent laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in patients with ESRD was an independent risk factor for mortality. Therefore, patients with acute cholecystitis must be treated before exacerbation of the inflammation. To avoid operative complications, Gunay et al. [46] suggested percutaneous cholecystostomy as a bridging method or palliative option to treat acute cholecystitis in some selected chronic hemodialysis patients.

There were limitations to the current study. First, we were unable to demonstrate the cause of acute cholecystitis. As we were unable to differentiate between the subtypes of acute cholecystitis (i.e., emphysematous cholecystitis, acalculous cholecystitis) in our dataset, we could not find a relationship between ESRD and gallstone disease. Second, it is possible that a case diagnosed with cholecystitis, but not having surgery or having undergone gallbladder drainage, may have been excluded from both groups. Since 2003, the code for cholecystectomy can be confirmed in the data, so patients in the dialysis group and the control group belong to the definition of cholecystitis in this study, “Cholecystectomy with cholecystitis and histologically confirmed” were identified and excluded, and many dialysis patients underwent percutaneous cholecystostomy due to poor medical conditions with a high rate of readmission [46]. Because we used a cholecystectomy code for specifying acute cholecystitis, we did not include a cholecystostomy code at initiation, which might be an important limitation in our study. Third, we used a general Cox model to control the selected covariates. After the ‘proportional hazards’ assumption is confirmed, stratified Cox analysis should be performed rather than general Cox analysis for propensity score matching data. However, in the matching, the HR of the general Cox analysis is smaller than that of the stratified Cox analysis, and the HR is underestimated. Therefore, the result does not change even if the analysis method is different. However, because differences due to the size of the sample cannot be completely excluded, repeated studies are needed for validation. In addition, we could not evaluate individual data such as smoking history, body mass index, and laboratory values, which can contribute to acute cholecystitis with gallstones. Further randomized controlled studies would unveil the precise mechanism of the clinical course and mortality associated with acute cholecystitis in dialysis patients.

In conclusion, we found that patients undergoing dialysis have a higher incidence and risk of acute cholecystitis compared to the general population. As acute cholecystitis in a patient with dialysis is associated with high mobility and mortality rates, the possibility of developing a gallbladder disorder in patients with gastrointestinal problems should be considered in the dialysis clinic. Further investigations are required to explore the development of acute cholecystitis and gallstones in patients with ESRD.

Supplementary Materials

Notes

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from the Chungbuk National University in 2020.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: HC, SKK, JHH, GK

Data curation: MK

Formal analysis: HC, SKK, GK, MK

Funding acquisition: JHH

Writing – original draft: HC, SKK, JHH, JSL, GK

Writing–review & editing: HC, SKK, JHH

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.