Hemorrhagic cystitis with massive bleeding from nontyphoidal Salmonella infection: A case report

Article information

Abstract

Hemorrhagic cystitis is defined by lower urinary tract symptoms that include dysuria, hematuria, and hemorrhage and is caused by viral or bacterial infection or chemotherapeutic agents. Reports of hemorrhagic cystitis caused by non-typhoidal salmonella (NTS) are extremely rare.

We report a case of a 41-year-old man with hemorrhagic cystitis from NTS that caused massive bleeding and shock. The patient was hospitalized for uncontrolled diabetes and obstructive uropathy related to severe cystitis. A urine culture was positive for group D NTS. This case demonstrated that hemorrhagic cystitis in a patient with a risk factor such as diabetes can be a manifestation of local extra-intestinal NTS infection.

Introduction

Salmonellosis is an important food borne infection with clinical and public implications. As environmental and personal sanitation improves, the incidence of typhoidal salmonellosis tends to decrease, while the incidence of non-typhoidal salmonellosis markedly increases [1], [2].

The most common clinical manifestation of NTS is gastroenteritis, and the condition includes bacteremia, focal infection, and an asymptomatic carrier state [1]. Of the manifestations, urinary tract infection (UTI) is unusual and rare [3], [4], and occurs in immunocompromised individuals, including patients with a malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or diabetes mellitus and patients receiving corticosteroid therapy or treatment with other immunotherapeutic agents [2], [5]. UTI caused by NTS presents as either pyelonephritis or cystitis [2], [6], [7]; cases of hemorrhagic cystitis are extremely rare. We report a case of severe hemorrhagic cystitis caused by NTS that resulted in shock and syncope in a patient with uncontrolled diabetes.

Case report

A 41-year-old man came to the emergency room for a fever that had developed 10 days earlier, and was accompanied by pus-like urine. The patient had watery diarrhea and had lost five kilograms of weight in one month. He had been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus 5 years earlier and his blood sugar level was not well controlled. The patient was a baker, did not have any pets, and did not have a history of recent travel. On admission, his temperature was 38 °C, his blood pressure was 110/60 mm Hg, and his heart rate was 102 beats/min. His mental examination showed confusion. The tongue and lips indicated severe dehydration. The patient's heartbeat was rapid, but regular and without murmur. There was no tenderness on the abdomen and both costo-vertebral angle areas. A moderate degree of petechia was noted on both lower extremities. Arthritis or arthralgia was not presented. The prostate was not enlarged on rectal examination.

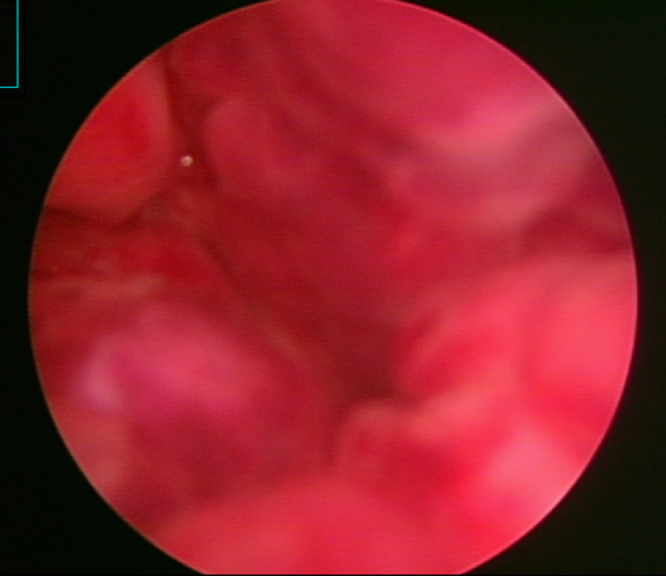

Laboratory findings showed leukocytes at 7100/mm3 which included 50% lymphocytes. Platelets were 209,000/mm3, hemoglobin was 13.6 g/dL, hematocrit was 40.9%, BUN/creatinine was 34.0/1.0 mg/dL, fasting/postprandial two-hour blood sugar was 330/482 mg/dL, and HbA1c was 11.1%. Coagulation studies including prothrombin time, partial prothrombin time revealed normal. C-reactive protein was elevated to 8.1 mg/dL. Urinary analysis revealed pyuria and microscopic hematuria. A Widal test showed a typhoid O titer of 1:1280 and typhoid H titer of 1:640, and a urine culture grew NTS (group D). No bacteria were isolated from the stool or blood culture. On abdomen-pelvis ultrasonography, the urinary bladder was filled with pus, the bladder wall was thickened diffusely (Fig. 1A), and hydronephrosis and hydroureter were observed on both sides of the bladder (Fig. 1B). The patient was treated with Foley catheter drainage and ceftriaxone/Amikin. The bacteria were later found to be sensitive to these drugs by culture study. The level of serum creatinine and urine output remained a consistent level during this period. However, the high fever and watery diarrhea continued.

Abdomen-pelvis ultrasonography on admission. (A) Urinary bladder shows hyperechogenic materials suggestive of pus, moving with body position change and a diffusely thickened bladder wall. (B) Bilateral hydronephrosis and hydroureter were observed.

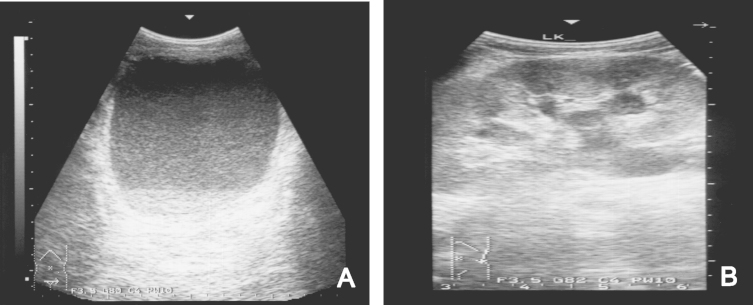

After 10 days in the hospital, the patient's urine output decreased suddenly and he developed severe lower abdominal distension and syncope. The patient's systolic blood pressure fell to 80 mm Hg and hemoglobin to 7.9 g/dL. An emergency CT scan showed that the urinary bladder was severely distended and filled with a mass suspicious of hematoma (Fig. 2). Also, both hydronephrosis were observed on the abdominal-pelvic CT. And then, cystoscopy was performed. Cystoscopic findings showed that bladder mucosa was hyperemic with multiple punctuated hemorrhage (Fig. 3). However, there was no stone, mass or focal mechanical injury, i.e foley catheter injury. A suprapubic percutaneous cystostomy was performed immediately, removing a massive fresh blood clot. Blood pressure was stabilized after transfusion of three packs of RBC and hemoglobin was elevated to 10.2 g/dL. The patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics and continuous bladder irrigation. He responded well to treatment and was discharged in good condition with oral antibiotics and oral hypoglycemic agents. Later, at an outpatient clinic, an intravenous pyelography showed no urological abnormality.

Abdomen-pelvis CT scan after 10 days in the hospital. Inhomogeneous mass suspicious of hematoma is observed in the distended urinary bladder.

Discussion

Despite improvements in individual and collective sanitation as well as the careful monitoring of food processing, sporadic episodes and outbreaks of salmonellosis continue to occur in industrialized countries [1]. The overall incidence of typhoidal salmonellosis has decreased, whereas that of non-typhoidal salmonellosis has increased [1], [2].

Non-typhoidal salmonellosis is a disease of great public health importance. Unlike S. typhi and S. paratyphi, whose only reservoirs are humans, NTS is acquired from multiple animal reservoirs. The main mode of transmission is from food products contaminated with animal products or waste, most commonly eggs and poultry, but also undercooked meat, unpasteurized dairy products, seafood, and fresh produce [3].

NTS is an enteroinvasive bacterium and causes infections that may have one of four different clinical presentations. The most common clinical manifestation of NTS is gastroenteritis (70%). However, invasion beyond the gastrointestinal tract occurs in approximately 5% of patients with NTS gastroenteritis, resulting in bacteremia [6]. Extraintestinal manifestations, which have a rare incidence of about 2–8%, include endocarditis, pericarditis, arteritis, soft tissue infection, UTI and pneumonia. Focal infection frequently occurs during or after Salmonella bacteremia. The gastrointestinal carrier state is the fourth clinical presentation and is defined as the excretion of NTS for months or years after the initial onset of disease.

UTI caused by NTS is so rare that it comprises only 0.01%–3% of positive urinary cultures [8], [9], [10] and 3% of NTS infections [11]. NTS has been postulated to enter the urinary tract either hematogenously or by direct invasion of fecal flora to the bladder via the urethra [11]. The risk factors of UTI caused by NTS include old age, chronic illness, immunosuppressive therapy and structural abnormality of the urinary tract [12]. Diabetes mellitus is also reported as a risk factor for Salmonella infection. UTI related to NTS presents as cystitis, pyelonephritis, renal abscess, or asymptomatic pyuria [3], [8]. A retrospective analysis of 28 cases of bacteriuria due to NTS showed that twenty-one patient (75%) had symptoms of UTI (16, cystitis; 3, pyelonephritis; and 2, renal abscess) [13]. Another review of nineteen patients with bacteriuria due to NTS showed that the frequency of UTI due to NTS was 0.07% (proportion of positive urine cultures). Eighteen patients (94.7%) had symptoms of UTI (12, cystitis; 6, pyelonephritis), and 1 remained asymptomatic [14]. However, case of hemorrhagic cystitis due to NTS was very rare. Furthermore, severe hemorrhagic cystitis caused by NTS with massive bleeding that resulted in shock and syncope was extremely rare.

UTI from Salmonella does not differ clinically from UTI caused by other members of the Enterobacteriaceae [15]. Our patient had uncontrolled diabetes for 5 years and had worked at a job in food handling for a long time. We are not sure of the mode of transmission in our patient's case; however, we propose that he might have been a Salmonella carrier or that his illness was caused by bacteremia from a previous gastrointestinal infection.

In uncomplicated Salmonella gastroenteritis, antibiotic therapy is not recommended because it does not shorten the disease duration. However, in cases of sepsis or local extraintestinal infection, prompt antibiotic administration is needed [1]. Traditionally, antibiotics such as ampicillin, amoxicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are used, but currently the frequency of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella isolates is increasing [1], [2]. In Korea, according to recent reports, group B Salmonella is the most common drug-resistant serotype, while the group D serotype has relatively low drug resistance [1]. Therefore, including third-generation cephalosporin and/or quinolone in empirical therapy is reasonable [2]. The treatment of focal extraintestinal Salmonella infection often requires both surgical drainage and antibiotic therapy in cases associated with structural abnormality of the urinary tract. Early surgical intervention might be combined with more prolonged therapy to eradicate UTI caused by NTS [3], [8].

In this report, we describe a case of hemorrhagic cystitis due to NTS, which caused massive bleeding, shock, and syncope in a patient with uncontrolled diabetes. The patient responded well to prolonged antibiotics and local drainage.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.