| Kidney Res Clin Pract > Volume 41(2); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

For the past 30 years, nephrologists have focused on a single minimal threshold of Kt/Vurea to determine the adequacy of peritoneal dialysis (PD). To date, there is no evidence that shows Kt/Vurea to be a good surrogate measure of uremic symptom control or nutritional state in patients on PD. Volume of distribution (Vurea) generally is considered equivalent to total body water (TBW). Yet, accurate determination of TBW is difficult. The most recent International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis practice recommendations on prescribing high-quality PD emphasized incorporation of multiple measures rather than the single value of Kt/Vurea. These measures include shared decision-making between the patient and the care team and assessment of health-related quality of life, burden of uremic symptoms, presence of residual kidney function, volume status, and biochemical measures including serum potassium and bicarbonate levels. In some cases, PD prescriptions can be tailored to the patient priorities and goals of care, such as in frail and pediatric patients. Overall, there has been a paradigm shift in providing high-quality care to PD patients. Instead of focusing on small solute clearance in the form of Kt/Vurea, nephrologists are encouraged to use a more comprehensive assessment of the patient as a whole.

For the past three decades, assessment of peritoneal dialysis (PD) adequacy has focused on a single minimal threshold of Kt/Vurea. The 1997 National Kidney Foundation-Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative clinical practice guidelines for PD adequacy recommended that weekly Kt/Vurea be at least 2.0 [1]. This recommendation was based predominantly on two observational studies. The CANUSA study included 680 incident patients on continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD) in Canada and the United States. The study demonstrated an inverse relationship between weekly Kt/Vurea and relative risk (RR) of death, with weekly Kt/Vurea of 2.1 associated with 78% expected 2-year survival [2]. Similarly, in an Italian study that evaluated prevalent CAPD patients, improved survival was observed in patients with weekly Kt/Vurea of Ōēź1.96 [3]. However, these findings were not supported by subsequent prospective randomized controlled trials.

The ADEMEX study included 965 patients on CAPD who were randomized either into a control group undergoing four exchanges with 2-L fill volume or an intervention group in which the prescription was modified to achieve a peritoneal creatinine clearance of 60 L/week/1.73 m2 [4]. The average total Kt/Vurea was 1.80 in the control group vs. 2.27 in the intervention group. After 2 years of follow-up, patient survival was equivalent between the two groups, with a RR of 1.0. Thus, increasing Kt/Vurea to Ōēź2.0 was not associated with survival benefit. Another clinical trial performed in Hong Kong evaluated 320 CAPD patients who were randomized into one of three groups targeting Kt/Vurea of 1.5 to 1.7, 1.7 to 2.0, and >2.0 [5]. There were no significant differences in patient survival, hospitalization rate, or serum albumin among the three groups after 2 years. However, more patients in the lowest Kt/Vurea target group (i.e., 1.5ŌĆō1.7) required erythropoietin treatment. Based on these studies, the 2006 International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) guidelines on PD recommended that the total (renal + peritoneal) Kt/Vurea not be less than 1.7 at any time [6].

Using Kt/Vurea to determine adequacy of PD poses several problems. To date, there is no evidence that prescribed peritoneal Kt/Vurea is a good surrogate measure of uremic symptom control or nutritional state in PD patients. There also are problems intrinsic to the measure itself. Volume of distribution of urea (Vurea) generally is considered equivalent to total body water (TBW), given that urea is highly soluble in both water and cell membranes but not adipose tissue. This assumption implies that V should be determined using ideal body weight rather than actual body weight to avoid overdialysis in obese patients and underdialysis in underweight patients. Unfortunately, determination of TBW is difficult. In a recent review article, Davies and Finkelstein [7] compared the three main methods used to estimate TBW: the gold-standard isotope dilution, bioimpedance, and anthropometric equations. They found wide limits of agreement among the methods. When comparing the commonly used anthropometric equations to isotope dilution, the 95% confidence interval was ┬▒18% of the TBW [7]. This translates into a Kt/Vurea range of 1.44 to 2.06 in an individual with a measured Kt/Vurea of 1.7 whose TBW is 35 L. Based on this finding, the authors suggest that a Kt/Vurea target for an individual patient should be defined as an acceptable range that considers the uncertainty of the measurement rather than applying a single cutoff value. Furthermore, a recent report from the SONG-PD study group described the 10 most important outcomes for patients on PD and their caregivers: infection, mortality, fatigue, flexibility with time, blood pressure, PD failure, ability to travel, sleep, ability to work, and effect on family [8]. In contrast, dialysis solute clearance was ranked the 52nd of 56 outcomes.

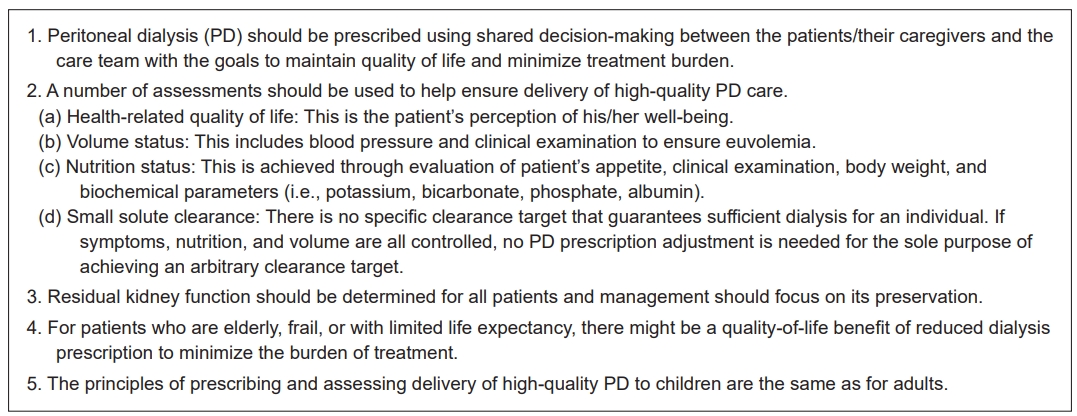

In 2020, the ISPD published updated practice recommendations for high-quality PD, which emphasized incorporation of multiple measures to assess the quality of dialysis rather than focusing on the single value of Kt/Vurea [9]. These measures include shared decision-making between the patient and care team and assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL), uremic symptoms, residual kidney function (RKF), volume status, biochemical measures, nutritional status, and small solute clearance. Highlights of these practice recommendations are outlined in Fig. 1.

An integral part of providing high-quality dialysis therapy is to understand the patientŌĆÖs priorities and goals of care and to utilize shared decision-making between patients and the care team [10]. This approach enables establishment of realistic care goals and expectations and allows clinicians to individualize care plans to maximize patient HRQOL. The relationship between amount of dialysis delivered and its impact on HRQOL is unclear. It is clear, however, that increasing the dose of dialysis did not correlate with improved clinical outcomes of PD patients in the Hong Kong study or the ADEMEX trial [4,5]. There is no evidence showing that increased dialysis delivery corresponds to improved HRQOL in PD patients. Furthermore, intensifying PD prescriptions by increasing the number of exchanges or duration of treatment can impact negatively on patient HRQOL. Thus, the most recent recommendation is that, in the absence of clinical symptoms and when volume and electrolytes are controlled, no PD prescription adjustment is needed for the sole purpose of reaching an arbitrary clearance target [9].

In contrast to Kt/Vurea, there are several clinical and biochemical parameters for which achieving certain levels do appear to be associated with superior outcomes. A recent review article by Teitelbaum proposed the following clinical parameters and biochemical levels to target: systolic blood pressure, 111 to 159 mmHg; absence of rales and lower extremity edema on exam; serum albumin, Ōēź3.8 g/dL; serum potassium, 4.0 to 5.4 mEq/L; serum sodium, Ōēź135 mEq/L; serum bicarbonate, Ōēź24 mEq/L; hemoglobin, Ōēź11g/dL; corrected serum calcium, 8.5 to 10.1 mg/dL; and serum phosphorus, Ōēż6.3 mg/dL [11].

Volume overload is a frequent complication in PD patients and is associated with adverse clinical outcomes. In a large European PD cohort study that included 639 patients from six countries, severe fluid overload was found in 25% of the patients [12]. Similarly, observational studies from Korea and China found the prevalence of volume overload in their PD patients to range from 27% to 67% [13,14]. In the Chinese study, the rate of cardiac events was significantly higher in patients with volume overload [14]. In the Korean study, chronic volume overload was associated with increased mortality [13]. A more recent systematic review including 42 cohorts of 60,790 patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), of which 5% were on PD, showed that an overhydration index of >15% is an independent predictor of mortality (hazard ratio, 2.28) [15]. On the other hand, overly aggressive volume removal in PD patients can cause accelerated loss of RKF. The NECOSAD study in the Netherlands showed that dehydration was associated with more rapid decline in RKF in PD patients [16]. Incident PD patients who experienced hypotensive episodes, most commonly caused by excessive ultrafiltration, were found to lose RKF more rapidly [17]. Nevertheless, volume expansion did not lead to preservation of RKF and was found to negatively impact RKF in some studies [18ŌĆō20]. Prescriptions of PD should aim to achieve and maintain clinical euvolemia while considering RKF and its preservation [21].

Maintaining electrolyte homeostasis and acid-base balance should be an important focus in the management of ESKD patients. Hypokalemia is common in PD patients because most PD dialysates do not contain potassium. The prevalence of hypokalemia (defined by serum potassium of <3.5 mEq/L) among PD patients ranges from 20% to 34% [22ŌĆō24]. Hypokalemia has been associated with poor nutritional status and higher comorbidity score [22]. It is also an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [22,23]. Moreover, in a retrospective Taiwanese cohort study, the prevalence of peritonitis was significantly higher in patients with hypokalemia compared to those without hypokalemia [25]. Management of hypokalemia in PD patients includes increased dietary potassium intake, use of oral potassium supplements, and use of potassium-sparing diuretics [26]. As discussed above, a serum potassium target in the range of 4.0 to 5.4 mEq/L is desired.

Persistent metabolic acidosis promotes protein catabolism, leading to selective breakdown of skeletal muscle protein, depression of myocardial contractility, and bone resorption [27ŌĆō29]. In a large cohort study that included 121,351 prevalent ESKD patients undergoing dialysis at DaVita facilities, prevalence of metabolic acidosis (defined as serum bicarbonate of <22 mEq/L) was 25% in PD patients [30]. The adjusted risk for all-cause mortality was higher in patients with serum bicarbonate of <22 mEq/L, irrespective of dialysis modality [30]. Two clinical trials examined the clinical benefits of correction of acidosis in PD patients. A group from the United Kingdom randomized patients into two groups; high alkali dialysate (lactate of 40 mmol/L) with oral bicarbonate supplement or low alkali dialysate (lactate of 35 mmol/L) [31]. At 1-year follow-up, patients in the high alkali dialysate group had greater increase in mid-arm circumference, higher weight gain, and fewer hospital admissions than the low alkali dialysate group. Another study from Hong Kong randomized assigned patients to either an oral sodium bicarbonate group (900 mg, three times daily) or placebo group [32]. At 12-month follow-up, patients in the treatment group had better nutritional status, higher body muscle mass, and fewer hospital days compared to the placebo group [32]. Management of metabolic acidosis can include either oral sodium bicarbonate supplement or intensifying PD prescriptions.

As previously mentioned, efforts should be made to avoid compromising RKF, since several observational studies have demonstrated that maintenance of RKF is associated independently with increased survival in patients with ESKD. A 40% decrease in RR of death for each 10 L/week/1.73 m2 increase in renal creatinine clearance was observed in patients on PD [33]. In a reanalysis of the CANUSA study, there was a 12% decrease in the RR of death with each 5 L/week/1.73 m2 increment in glomerular filtration rate, while there was no association between higher peritoneal creatinine clearance and risk of death [34]. Declining RKF is one of the predictors of uncontrolled blood pressure in PD patients, suggesting that euvolemia is more difficult to achieve with loss of RKF [35]. Moreover, Wang et al. [36] found greater use of antihypertensive agents and higher left ventricular mass index in anuric PD patients. In the same study, the authors also found that anuric patients, compared to those with RKF, are more likely to have anemia, erythropoietin requirements, higher C-reactive protein level, hypoalbuminemia, and malnutrition. It is important to recognize that, while intensifying the PD prescription might compensate for the loss of urea clearance with declining RKF, it will not replace all functions of failing native kidneys. Therefore, preservation of RKF is an important therapeutic endpoint in management of PD patients and should be taken into consideration when evaluating the quality of a PD prescription.

As discussed earlier, provision of high-quality dialysis therapy requires an understanding of the patientŌĆÖs priorities and goals of care. Two specific patient populations deserve special mention. Frailty presents as a composite of poor physical function, decreased physical activity, fatigue, and weight loss and is associated with increased risks of falls, cognitive impairment, hospitalization, and mortality [37]. Frailty is found more commonly in older patients with ESKD. The goal of providing PD to frail patients is to improve overall well-being while minimizing treatment burden. For example, PD prescription can be reduced by performing fewer exchanges or allowing days off to maximize quality of life, especially when RKF is present [38]. At the other end of the spectrum, in pediatric patients, selection of dialysis modality should be based on parent/caregiver choice, child age and size, availability of family support, and modality contraindications [39]. In general, the same principles used to assess the delivery of high-quality PD care in adult patients should be applied to pediatric patients [39].

Thus, the 2020 ISPD practice recommendations do indeed represent a paradigm shift. Rather than focusing on small solute clearance in the form of Kt/Vurea, these recommendations require a more comprehensive assessment of the patient as a whole. Clinicians are encouraged to embrace this change and provide patients with the highest possible quality of care.

Figure┬Ā1.

Highlights of the 2020 International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis key practice recommendations on prescribing high-quality goal-directed peritoneal dialysis.

Adapted from Brown et al. [9] according to the Creative Commons License.

References

1. National Kidney Foundation. NKF-DOQI clinical practice guidelines for peritoneal dialysis adequacy. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;30(3 Suppl 2):S67ŌĆōS136.

2. Canada-USA (CANUSA) Peritoneal Dialysis Study Group. Adequacy of dialysis and nutrition in continuous peritoneal dialysis: association with clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 1996;7:198ŌĆō207.

3. Maiorca R, Brunori G, Zubani R, et al. Predictive value of dialysis adequacy and nutritional indices for mortality and morbidity in CAPD and HD patients: a longitudinal study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1995;10:2295ŌĆō2305.

4. Paniagua R, Amato D, Vonesh E, et al. Effects of increased peritoneal clearances on mortality rates in peritoneal dialysis: ADEMEX, a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002;13:1307ŌĆō1320.

5. Lo WK, Ho YW, Li CS, et al. Effect of Kt/V on survival and clinical outcome in CAPD patients in a randomized prospective study. Kidney Int 2003;64:649ŌĆō656.

6. Lo WK, Bargman JM, Burkart J, et al. Guideline on targets for solute and fluid removal in adult patients on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2006;26:520ŌĆō522.

7. Davies SJ, Finkelstein FO. Accuracy of the estimation of V and the implications this has when applying Kt/Vurea for measuring dialysis dose in peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2020;40:261ŌĆō269.

8. Manera KE, Johnson DW, Craig JC, et al. Patient and caregiver priorities for outcomes in peritoneal dialysis: multinational nominal group technique study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019;14:74ŌĆō83.

9. Brown EA, Blake PG, Boudville N, et al. International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis practice recommendations: prescribing high-quality goal-directed peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2020;40:244ŌĆō253.

10. Finkelstein FO, Foo MW. Health-related quality of life and adequacy of dialysis for the individual maintained on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2020;40:270ŌĆō273.

11. Teitelbaum I. Delivering high-quality peritoneal dialysis: what really matters? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;15:1663ŌĆō1665.

12. Van Biesen W, Williams JD, Covic AC, et al. Fluid status in peritoneal dialysis patients: the European Body Composition Monitoring (EuroBCM) study cohort. PLoS One 2011;6:e17148.

13. Kim JK, Song YR, Lee HS, Kim HJ, Kim SG. Repeated bioimpedance measurements predict prognosis of peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 2018;47:120ŌĆō129.

14. Guo Q, Yi C, Li J, Wu X, Yang X, Yu X. Prevalence and risk factors of fluid overload in Southern Chinese continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. PLoS One 2013;8:e53294.

15. Tabinor M, Elphick E, Dudson M, Kwok CS, Lambie M, Davies SJ. Bioimpedance-defined overhydration predicts survival in end stage kidney failure (ESKF): systematic review and subgroup meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2018;8:4441.

16. Jansen MA, Hart AA, Korevaar JC, et al. Predictors of the rate of decline of residual renal function in incident dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2002;62:1046ŌĆō1053.

17. Liao CT, Chen YM, Shiao CC, et al. Rate of decline of residual renal function is associated with all-cause mortality and technique failure in patients on long-term peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:2909ŌĆō2914.

18. McCafferty K, Fan S, Davenport A. Extracellular volume expansion, measured by multifrequency bioimpedance, does not help preserve residual renal function in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2014;85:151ŌĆō157.

19. Davenport A, Sayed RH, Fan S. Is extracellular volume expansion of peritoneal dialysis patients associated with greater urine output? Blood Purif 2011;32:226ŌĆō231.

20. Fan S, Sayed RH, Davenport A. Extracellular volume expansion in peritoneal dialysis patients. Int J Artif Organs 2012;35:338ŌĆō345.

21. Wang AY, Dong J, Xu X, Davies S. Volume management as a key dimension of a high-quality PD prescription. Perit Dial Int 2020;40:282ŌĆō292.

22. Szeto CC, Chow KM, Kwan BC, et al. Hypokalemia in Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients: prevalence and prognostic implication. Am J Kidney Dis 2005;46:128ŌĆō135.

23. Xu Q, Xu F, Fan L, et al. Serum potassium levels and its variability in incident peritoneal dialysis patients: associations with mortality. PLoS One 2014;9:e86750.

24. Hamad A, Hussain ME, Elsanousi S, et al. Prevalence and management of hypokalemia in peritoneal dialysis patients in Qatar. Int J Nephrol 2019;2019:1875358.

25. Chuang YW, Shu KH, Yu TM, Cheng CH, Chen CH. Hypokalaemia: an independent risk factor of Enterobacteriaceae peritonitis in CAPD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:1603ŌĆō1608.

26. F├╝l├Čp T, Zsom L, Rodr├Łguez B, et al. Clinical utility of potassium-sparing diuretics to maintain normal serum potassium in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 2017;37:63ŌĆō69.

27. Mehrotra R, Kopple JD, Wolfson M. Clinical utility of potassium-sparing diuretics to maintain normal serum potassium in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int Suppl 2003;(88):S13ŌĆōS25.

28. May RC, Bailey JL, Mitch WE, Masud T, England BK. Glucocorticoids and acidosis stimulate protein and amino acid catabolism in vivo. Kidney Int 1996;49:679ŌĆō683.

30. Vashistha T, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Molnar MZ, Torl├®n K, Mehrotra R. Dialysis modality and correction of uremic metabolic acidosis: relationship with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:254ŌĆō264.

31. Stein A, Moorhouse J, Iles-Smith H, et al. Role of an improvement in acid-base status and nutrition in CAPD patients. Kidney Int 1997;52:1089ŌĆō1095.

32. Szeto CC, Wong TY, Chow KM, Leung CB, Li PK. Oral sodium bicarbonate for the treatment of metabolic acidosis in peritoneal dialysis patients: a randomized placebo-control trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:2119ŌĆō2126.

33. Rocco M, Soucie JM, Pastan S, McClellan WM. Peritoneal dialysis adequacy and risk of death. Kidney Int 2000;58:446ŌĆō457.

34. Bargman JM, Thorpe KE, Churchill DN. Relative contribution of residual renal function and peritoneal clearance to adequacy of dialysis: a reanalysis of the CANUSA study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001;12:2158ŌĆō2162.

35. Menon MK, Naimark DM, Bargman JM, Vas SI, Oreopoulos DG. Long-term blood pressure control in a cohort of peritoneal dialysis patients and its association with residual renal function. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001;16:2207ŌĆō2213.

36. Wang AY, Woo J, Wang M, et al. Important differentiation of factors that predict outcome in peritoneal dialysis patients with different degrees of residual renal function. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005;20:396ŌĆō403.

37. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381:752ŌĆō762.

-

METRICS

- ORCID iDs

-

Chang Huei Chen

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4515-1964Isaac Teitelbaum

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7526-6837 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print