An update on renal fibrosis: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies with a focus on extracellular vesicles

Article information

Abstract

The increasing prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major global public health concern. Despite the complicated pathogenesis of CKD, renal fibrosis represents the most common pathological condition, comprised of progressive accumulation of extracellular matrix in the diseased kidney. Over the last several decades, tremendous progress in understanding the mechanism of renal fibrosis has been achieved, and corresponding potential therapeutic strategies targeting fibrosis-related signaling pathways are emerging. Importantly, extracellular vesicles (EVs) contribute significantly to renal inflammation and fibrosis by mediating cellular communication. Increasing evidence suggests the potential of EV-based therapy in renal inflammation and fibrosis, which may represent a future direction for CKD therapy.

Introduction

Due to the increased risk of end-stage renal disease and its devastating effects on the cardiovascular system, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with high morbidity and mortality. There is a growing global burden of CKD, affecting 10% of adults worldwide; meanwhile, the global mortality rate attributed to CKD has increased by 41.5% in the last three decades [1,2]. Tubulointerstitial fibrosis, a defining feature of CKD, is characterized by extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation and renal scarring, which lead to both structural and functional deterioration of the kidneys. The fibrogenesis process includes inflammatory cell infiltration, excessive fibroblast activation, overwhelming ECM deposition, tubular atrophy, and renal microvasculature rarefaction. Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) have enabled tremendous progress in understanding the mechanisms behind renal fibrosis.

In past decades, clinically available pharmacological interventions for delaying CKD progression have been primarily restricted to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is the master regulator of fibrosis, and new agents that target the TGF-β signaling pathway are continually emerging. Particularly, there is mounting evidence supporting the critical role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in renal physiology and pathology. EVs are considered key mediators of cellular communication participating in renal fibrosis progression. Importantly, EVs are promising therapeutic vectors due to their intrinsic contents and natural nanocarrier properties for small-molecule drugs as well as genetic therapies.

The purpose of this review is to provide new insights into the mechanisms of renal fibrosis, as well as prospective therapeutic approaches targeting pathological signaling and cellular events. The important role of EVs will be emphasized regarding the mechanisms and therapy of renal fibrosis.

Pathogenesis of renal fibrosis

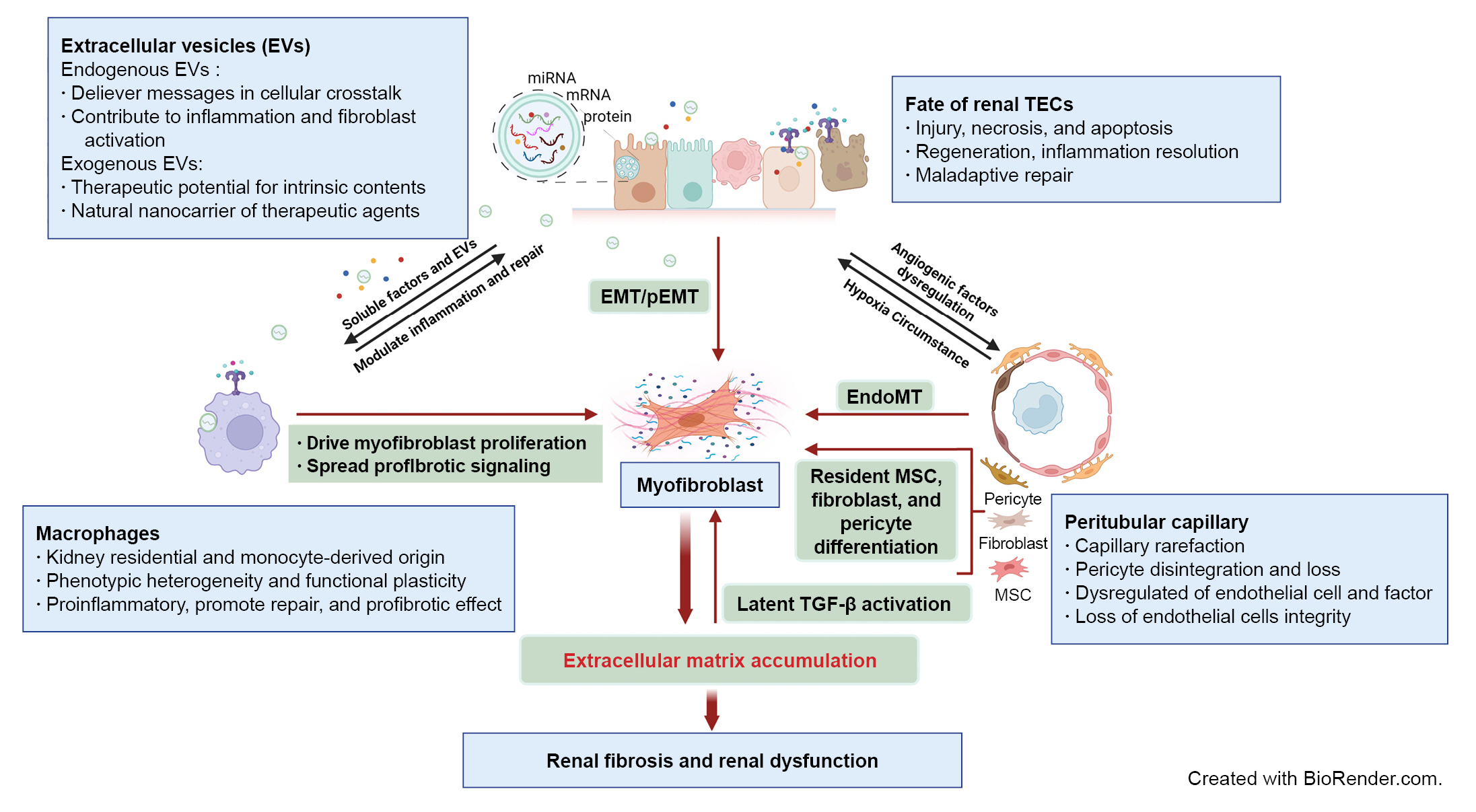

An overview of the complex interplays and critical events involved in renal fibrosis progression is shown in Fig. 1.

Schematic elucidation of cellular and signaling events in renal fibrosis.

Renal tubule injury acts as a driving force in fibrosis progression through communication with immune cells, peritubular capillary (PTC), and interstitial stroma cells via soluble or extracellular vesicle (EV) signaling. Persistent or severe injury leads to maladaptive repair of tubular epithelial cells (TECs) and subsequent EMT or pEMT, contributing to renal fibrosis. PTC rarefaction generates a hypoxic environment that promotes tubular atrophy. The phenotypic heterogeneity and functional plasticity elucidate the versatile roles of macrophages during inflammation, tissue repair, and fibrosis. Excessive accumulation of ECM components contributes to overactivation of myofibroblasts originating from multiple cellular sources and provides a substrate for latent transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) activation. Endogenous EVs play a notable role in delivery of messages in cellular communication, while exogenous EVs are being developed as new therapeutic agents for renal fibrosis.

AKI, acute kidney injury; ECM, extracellular matrix; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; EndoMT, endothelial-mesenchymal transition; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; pEMT, partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

Maladaptive repair of tubule epithelial cells

Tubule epithelial cells (TECs) undergo adaptive and maladaptive repair after injury, which is crucial for determining whether kidney injury will be repaired or progress to CKD [3]. In most circumstances, however, residual inflammatory and fibrotic processes continue to propel disease progression despite recovery of renal function to baseline after acute injury [4]. In acute kidney injury (AKI), various damage-associated molecular patterns released from injured TECs interact with pattern recognition receptors on TECs, leading to production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines by the TECs and massive immune cell infiltration [5]. In turn, activated immune cells, especially macrophages, induce further TEC injury and necrosis [5,6]. Unresolved or excessive tubulointerstitial inflammation can lead to persistent kidney injury, which plays a central role in maladaptive repair of TECs.

A process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) after injury has long been recognized and contributes to renal fibrosis as epithelial cells switch to mesenchymal cells [7]. However, whether epithelial cells undergo complete EMT and become matrix-producing cells depends on the condition of tissues and persistence of cytokine production [7]. Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that dedifferentiated TECs remained adherent to the membrane and express markers of both epithelial and mesenchymal cells, a phenomenon called partial EMT (pEMT), contributing to renal fibrogenesis [8]. Importantly, injured and dedifferentiated proximal tubular cells are responsible for tissue repair other than fixed tubular progenitor cells, and proliferation of proximal tubules might be regulated by the EGFR-FOXM1 signaling pathway [9].

Recently, several scRNA-seq analyses further verified that maladaptive repair of TECs accelerates renal fibrosis. The scRNA-seq of a mouse AKI model identified a distinct proinflammatory and profibrotic role of failed-repair proximal tubule cells [10]. Another study found that maladaptive repair of proximal tubules could accelerate progressive interstitial fibrosis, which consequently promotes pericyte activation, peritubular capillary (PTC) loss, and matrix deposition [4]. In addition, new clusters of proximal tubular cells (present only following injury) with the ability to transfer pathological signaling to fibroblasts and macrophages were identified [11]. However, the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms of maladaptive repair remain to be fully elucidated.

Peritubular capillary rarefaction

PTC rarefaction along with tubular atrophy is commonly detected in renal fibrosis. The level of PTC loss correlates with the severity of fibrosis [12]. Animal experiments have confirmed in CKD models such as the remnant kidney model [13] and unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) [14] that capillary density was negatively correlated with fibrosis. An antiangiogenic environment including deprivation of endothelial cell survival factors, upregulation of anti-angiogenic factors, dysfunction of endothelial cells, and loss of endothelial cell integrity contributes to the rarefaction of PTC [15]. In addition, pericyte disintegration and loss after kidney injury promoted instability of blood vessel structure and further capillary rarefaction. To date, the mechanism of PTC rarefaction is not clearly identified. However, inflammatory macrophages can block expression of tubular vascular endothelial growth factor A by infiltration and secretion of inflammatory cytokines, especially interleukin (IL) 1β and tumor necrosis factor α [16]. This blockage is regarded as a core event for PTC rarefaction. Additionally, as a key feature in ischemic kidney injury, the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT) is depicted as the transition from typical endothelial cells to a profibrotic phenotype [17], which results in PTC rarefaction and CKD progression.

The versatile roles of macrophages

The phenotypic heterogeneity and functional plasticity elucidate the versatile roles of macrophages during tissue repair and fibrosis. Lineage tracing studies indicate that self-renewed kidney resident macrophages (KRMs) in adult kidneys largely originate from yolk sac erythro-myeloid progenitors (EMPs), fetal liver EMPs, and hematopoietic stem cells [18]. Once injury occurs, circulating monocytes from bone marrow infiltrate the kidney in inflammatory microenvironments [19]. A recent study demonstrated that KRMs and monocyte-derived infiltrated macrophages (IMs) play complementary functions in reducing tissue inflammation and fostering tissue repair [20].

Traditionally, IMs in kidney disease are grouped into either classically activated M1 macrophages associated with the TH1-like response or alternatively activated M2 macrophages that contribute to the TH2-like response. Specifically, M2 macrophages can be subdivided into three types based on diverse stimuli and functions [21]. Accumulation and activation of macrophages are directly related to kidney injury and fibrosis severity, and excessive profibrotic mediators secreted from M2 macrophages could drive myofibroblast proliferation and profibrotic signaling pathways [22]. Recent studies have illustrated that Ly6Chigh monocytes accumulate in the inflammatory kidney and differentiate into three subpopulations, including the proinflammatory CD11b+/Ly6Chigh population presented at the onset of renal injury, the CD11b+/Ly6Cint population dominant in the renal repair phase, and the profibrotic CD11b+/Ly6Clow population that emerges in renal fibrosis [23].

In scRNA-seq analysis, macrophage diversity can be deciphered unbiasedly or macrophage clusters can be explored according to phenotype and cell function, showing the complexity of macrophages [24]. For example, recent scRNA-seq research identified a unique population of S100A9hiLy6Chi IMs mediating the initiation and amplification of inflammation in AKI, and blockade of S100a8/a9 signaling exhibited renal protective effects in an ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) model [20]. Therefore, a precise understanding of the dynamics and functional characteristics of macrophages under different microenvironments could offer specific therapeutic targets for kidney diseases.

Activation of matrix-producing cells

Excessive ECM accumulation is the key characteristic of renal fibrosis, and studies have been conducted to define the cellular sources contributing to pathological deposition of ECM. Myofibroblasts are commonly regarded as the predominant matrix-producing cell in diseased kidneys [25]. Renal resident fibroblasts can transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts with reduced production of fibroblast-derived erythropoietin, leading to renal anemia and consequent CKD progression [26].

Traditionally, α-smooth muscle actin is considered the marker for myofibroblasts, while a recent scRNA-seq study proposed Postn as another identifier for myofibroblasts with high ECM production [27]. Interestingly, there is high heterogeneity of myofibroblasts in terms of cell origin and function, similar to diverse macrophages in diseased kidneys. scRNA-seq applied in human kidney fibrosis revealed that myofibroblasts mainly originate from diverse resident mesenchymal cells, primarily distinct fibroblast and pericyte populations, far more than from fibrocytes [27]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were previously proposed as contributors of myofibroblasts [28], and new evidence suggested that Gli1+ MSC-like cells represent a myofibroblast pool in response to injury and contribute to fibrosis development [29,30]. Although EMT and EndoMT are mechanisms involved in renal fibrosis, myofibroblasts from transdifferentiated renal tubular cells or endothelial cells have been reported to account for only a small fraction [27]. Overall, myofibroblasts are responsible for excessive ECM synthesis and deposition, and further research is needed to clarify the full map of matrix-producing cells during fibrosis development.

Myofibroblasts produce collagen fibers when activated, resulting in excessive ECM deposition. The remodeling of ECM is in an equilibrium process. The ongoing ECM protein synthesis and degradation are orchestrated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs), both of which are considered key enzymes responsible for remodeling of ECM. Thus, dysregulation of MMP/TIMP activity is associated with progression of renal fibrosis [31]. Interestingly, the mechanical structure of ECM is not simply a scaffold, but rather a substrate to bind growth factors, particularly latent TGF-β1. ECM is capable of activating TGF-β1 by supplying the necessary mechanical resistance. The latent TGF-β–binding protein (LTBP) covalently binds the latency-associated peptide (LAP) together with TGF-β to form the large latent complex. LTBPs interact with ECM components and localize latent TGF-β in the ECM. When integrins on the cell surface attach to the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) binding site of LAP, TGF-β1 is released and activated through tension generated between integrins and ECM [32]. Moreover, activation of latent TGF-β is enhanced as ECM stiffness increases, leading to increased TGF-β signaling [33,34].

Inflammation and fibrosis signaling activated by extracellular vesicles

EVs are small membrane vesicles of two major subtypes: exosomes (40 to 160 nm), which originate from endosomes, and ectosomes (50 nm to 1 μm), which are derived from direct plasma membrane budding [35]. Increasing evidence supports the idea that EVs selectively transfer specific signals to regulate organ development, immune responses, and disease. Therefore, understanding the signals transferred by EVs may help shed light on the mechanisms of renal fibrosis.

As the primary component of the tubulointerstitium, TECs are particularly vulnerable to injury, which accelerates renal disease progression. The secreted proinflammatory mediators then guide inflammatory cells, including monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and mast cells, to the injured sites to provoke inflammation and cell death [6,36]. Recent studies support a notable role of EVs in renal inflammation via mediation of tubular-macrophage crosstalk. After injury, TECs increase the secretion of EVs carrying proinflammatory-related cargoes, such as CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) messenger RNA (mRNA) and functional microRNA (miRNAs: miRNA-23a, miRNA-19b-3p, etc.), which are transferred to initiate macrophage activation and migration and augment tubulointerstitial inflammation [37–39]. In addition, EVs are essential signal messengers in the proximal-to-distal tubular communication in pathological conditions [40]. Moreover, EVs could also participate in renal fibrosis via communication with interstitial fibroblasts. Injured TEC-derived exosomes enriched with TGF-β1 mRNA promote fibroblast activation [41]. Furthermore, increasing reports suggest that EVs containing various miRNAs (miR-196b-5p, miR-150, and miR-21) can activate fibroblasts and intensify renal fibrosis [42–44]. Recently, tubular cell-derived exosomal osteopontin was identified as responsible for activation of fibroblasts and promotion of renal fibrosis development [45].

Therefore, EVs released from injured renal cells are loaded with signal molecules of inflammation and fibrosis, which favor amplification of unresolved and prolonged inflammatory proteins and further serve as a crucial trigger of tissue fibrogenesis.

Therapy of renal fibrosis

Emerging transforming growth factor-β–targeted treatment

Fibrosis is the ultimate common pathway for CKD in spite of the underlying etiology, and antifibrotic agents are crucial for treatment of CKD. Here, we mainly discuss emerging therapeutic options targeting TGF-β in renal fibrosis and CKD.

TGF-β is linked with fibrosis of various organs. Previous evidence demonstrated that TGF-β participates in pathological fibrosis processes, including mediating ECM dysregulation, transdifferentiation of intrinsic cells, and mesangial cell proliferation. Therefore, TGF-β signaling represents a critical target for renal fibrosis.

Pirfenidone is a small synthetic inhibitor that blocks the TGF-β promotor and has antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory properties. It has been widely used for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treatment in clinical studies [46]. In many animal models of renal disease, pirfenidone also exerts similar effects [47], however, its potential in clinical settings remains to be investigated. The ongoing TOP-CKD trial (NCT04258397), the largest pirfenidone phase II study enrolling 200 participants, is estimated to be completed by December 2024. Similarly, pentoxifylline, a clinically available drug, was reported to downregulate TGF-β1 expression, delay progression of CKD, and reduce cardiovascular risk [48].

Compared to TGF-β deficiency probably causing severe immune dysregulation, antibody neutralization of TGF-β is recognized to have higher security with fewer adverse effects. Multiple preclinical investigations have revealed that direct TGF-β neutralization could halt the development of fibrosis. Fresolimumab and LY2382770, human monoclonal antibodies that neutralize TGF-β1, have been evaluated in phase Ⅱ trials in patients with steroid-resistant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and diabetic nephropathy, respectively [49,50]. Unfortunately, neither achieved the expected clinical outcome, which may need to be confirmed by larger and more robust studies. Since integrin αvβ6 can activate latent TGF-β, targeted integrin αvβ6 blockade by antibodies or small molecules offers an option for inhibition of TGF-β-induced fibrosis. The monoclonal antibody STX-100 (BG00011), which specifically blocks integrin αvβ6, has shown potential as an antifibrotic medication [51]. A phase II study with STX-100 (NCT00878761) administered to individuals with chronic allograft dysfunction, however, resulted in discontinuation for unknown reasons.

To avoid adverse events caused by a complete blockade of TGF-β, selective blockers of the TGF-β downstream signaling pathway have attracted increasing attention. Further basic research and clinical trials are required to discover a precise approach to TGF-β inhibition.

Potential application of extracellular vesicles in renal fibrosis therapy

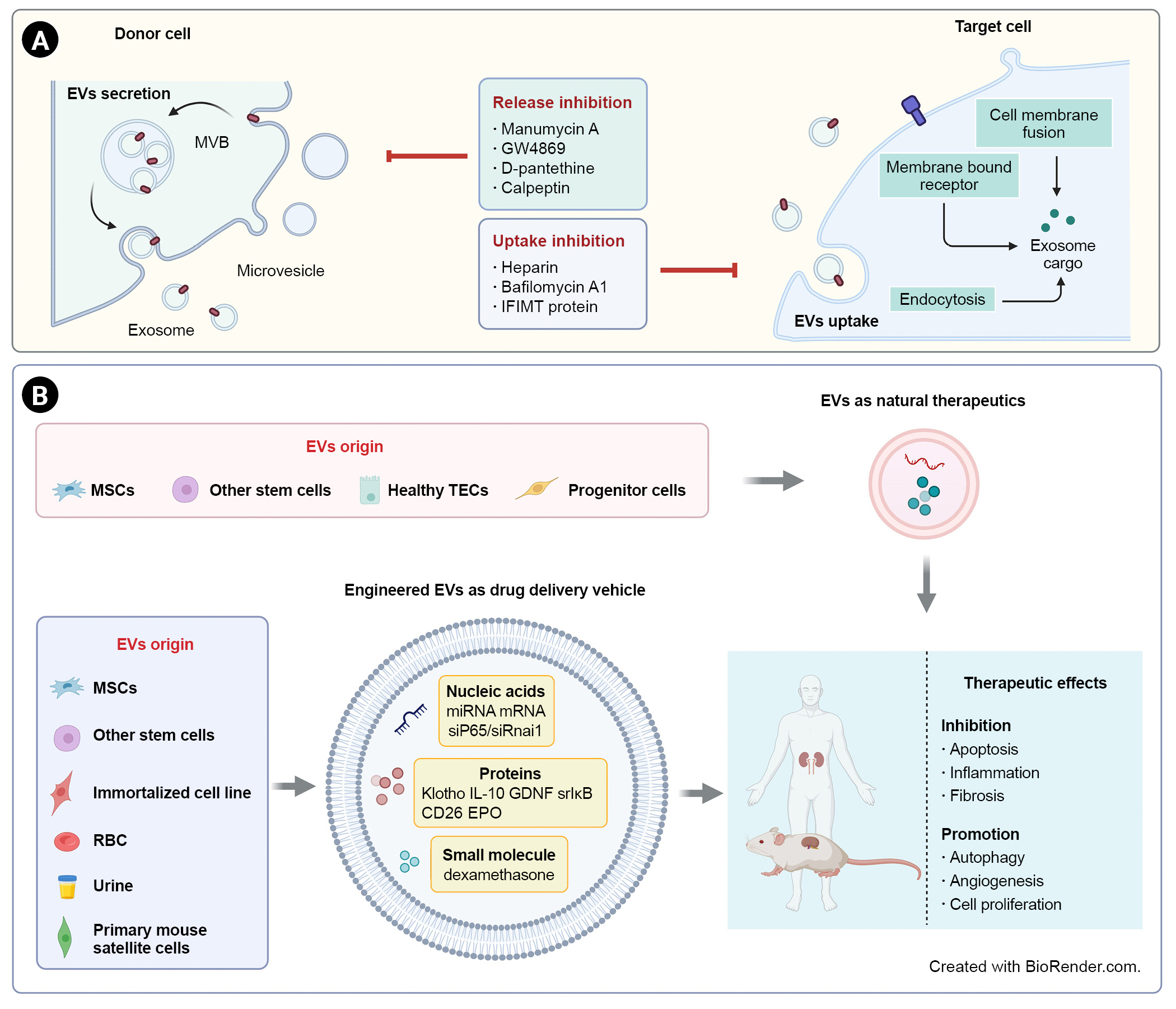

Increasing evidence suggests that pathological signaling delivered by EVs could be essential for tubulointerstitial communication in renal inflammation and fibrosis [38]. Therefore, inhibition of endogenous damage-associated EVs is a potential therapeutic strategy. Moreover, the therapeutic functions of MSC-derived EVs have given rise to increasing interest due to their intrinsic contents. Notably, EVs could also act as a natural “Trojan horse” to deliver a variety of drugs to treat kidney diseases. Schematic EV-based therapeutic strategies for renal fibrosis are shown in Fig. 2.

EV-based therapeutic strategies for renal fibrosis.

(A) Due to the pathological effects of EVs in renal inflammation and fibrosis, inhibition of EV secretion or uptake is a potential strategy for kidney diseases. (B) EVs derived from stem cells or healthy renal intrinsic cells could act as direct natural therapeutics. EVs can also be used as delivery vehicles for a variety of drugs, including nucleic acids, proteins, and small molecules. EV-based treatments have shown therapeutic effects on renal fibrosis through inhibition of apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis and promotion of autophagy, angiogenesis, and proliferation.

EVs, extracellular vesicles; EPO, erythropoietin; GDNF, glial-derived neurotrophic factor; IL, interleukin; miRNA, microRNA; mRNA, messenger RNA; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; MVB, multivesicular body; RBC, red blood cell; srIκB, super-repressor IκB; TECs, tubular epithelial cells.

Inhibition of pathogenic extracellular vesicles

EVs are secreted by parent cells and travel to neighboring or remote sites to exert their function, a process that could be inhibited by targeting the release and uptake of EVs. Pharmacologically, a number of agents have been demonstrated to inhibit EV secretion through different mechanisms. Manumycin A, the most widely used farnesyltransferase inhibitor, is necessary for exosome synthesis in the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent pathway and has been shown in an in vitro model to block exosome release to support the repair of damaged renal epithelium [52,53]. GW4869 is a blockade of neutral sphingomyelinase (nSMase), which mediates ESCRT-independent intraluminal vesicle formation, and has been widely reported as a pharmacological agent to inhibit exosome release in various cancers as well as kidney diseases. Reduced exosome secretion after GW4869 treatment inhibited fibroblast activation and ECM deposition in unilateral IRI in mice [54]. Phosphatidylserine externalization plays a crucial role in membrane budding and formation of microvesicles (MVs). The pantothenic acid derivative pantethine was demonstrated to impair MV release by preventing the transfer of phosphatidylserine. In an experimental model, mice treated orally with D-pantethine showed alleviation of fibrosis, and such a protective function might be associated with reduction of endothelial-derived MVs in circulation [55]. Calpain could be activated by calcium to regulate cytoskeleton remodeling and then increase MV release. As a calpain inhibitor, calpeptin treatment could reduce bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting EMT-related markers and the TGF-β1 signaling pathway, which might be related to MV reduction [56].

EVs are significant intercellular communication mediators that interact with recipient cells in an autocrine, paracrine, or endocrine manner [57] through three mechanisms: membrane fusion, receptor (direct) interaction, and internalization [58]. Hence, they may provide an alternative method to inhibit exosome function by blocking uptake. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) participate in the internalization of cancer cell-derived exosomes, which depend on intact HSPG synthesis and HS sulfation in target cells. Heparin as an HS mimetic inhibits exosome uptake dose dependently [59]. In addition, Bonsergent et al. [60] found that EV uptake is a slow process by quantification analysis, and content delivery can be inhibited by bafilomycin A1 and IFIMT protein overexpression in a pH-dependent manner.

Due to the heterogeneity of EVs and recipient cells, further investigation is warranted to clarify the precise mechanism of formation and uptake of EVs for developing precise therapeutic strategies targeting pathogenic EVs.

Utilization of mesenchymal stem cell-extracellular vesicles as therapeutic agents

Remarkable therapeutic effects of anti-inflammation, antifibrosis, and proregeneration have been demonstrated by MSCs for treatment of kidney disease. However, there are safety issues related to immune responses, toxicity, and carcinogenicity [61]. MSCs function in a paracrine or endocrine manner and are coordinated by secretomes, growth factors, cytokines, and EVs [62]. Compared to MSCs, EVs derived from MSCs are characterized by higher safety, lower immunogenicity, easier preservation, and genetic stability.

A growing number of studies are exploring the potential properties of MSC-EVs in CKD models. Intravenous administration of EVs derived from bone marrow MSCs (BM-MSC) ameliorated tubular necrosis and interstitial fibrosis and improved renal function in a mouse model of aristolochic acid-induced nephropathy [63]. EVs originated from BM-MSCs and human liver stem-like cells also attenuated fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy due to modulation of fibrosis-related gene expression by miRNA cargoes [64]. In a clinical pilot study involving 40 CKD patients with eGFR between 15 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, both intravenous and intraarterial administration of cell-free MSC-EVs from umbilical cord blood regulated immune response and improved renal function [65]. EVs containing miR-26a-5p from adipose-derived MSCs protected against diabetic nephropathy by targeting toll-like receptor 4 [66]. Additionally, exosomes of human umbilical cord MSCs have been shown to promote nuclear YAP shuttle to cytoplasm and to reduce matrix accumulation by transporting casein kinase 1 δ and β-TRCP to target cells [67]. Interestingly, human urine-derived stem cell exosomes protected against diabetic nephropathy by reducing apoptosis of podocytes and enhancing angiogenesis and cell survival [68].

In conclusion, MSC-EVs may become an alternative therapeutic tool for kidney disease, and further research should be conducted to promote the transition of MSC-EVs to clinical application.

Extracellular vesicles as therapeutic delivery vehicles

As natural membrane structures, EV capacity to transfer biomolecules to recipient cells has attracted considerable attention for its potential to overcome limitations of liposomes and other synthetic drug delivery systems. EV-based therapies offer many outstanding advantages due to the natural lipid structure and modifiable membrane properties achieved through manipulation of parent cells to improve stability as well as by targeting specific tissues and cells [69].

Endogenous and exogenous loading are two principal approaches to integrate therapeutic drugs into exosomes [70]. The technical methodology can be found in another published review [71]. Here, we summarize the studies regarding application of EVs as a therapeutic agent delivery system in renal disease (Table 1) [72–90].

Molecular drugs

EVs have been extensively used as delivery vectors for small molecules in recent studies. Curcumin carried by exosomes had excellent biological function in terms of solubility, stability, and bioavailability. Curcumin encapsulated by exosomes exerted anti-inflammatory effects in lipopolysaccharide-induced brain inflammation and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [91]. Additionally, exosome-loaded doxorubicin showed less accumulation in off-target tissues and was less cardiotoxic than unmodified doxorubicin [92,93]. Dexamethasone-loaded macrophage-derived MVs exhibited superior anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic activity without apparent glucocorticoid adverse effects [72], suggesting the possibility of EVs for drug transfer in renal disease.

Therapeutic proteins

Exosomes have an intrinsic capacity to cross biological barriers. Macrophage-derived exosomes without modification can penetrate the blood-brain barrier to transfer brain-derived neurotrophic factor to the central nervous system [94]. Recently, we successfully constructed IL-10-loaded EVs by engineering macrophages to target the injured kidney, which significantly improved renal tubular injury and inflammation and prevented the transition to CKD [73]. Concerning the stability and validity of large molecular cargoes, however, there are technical obstacles to efficiently load proteins into EVs. Increasing attempts had been made to solve this problem; for example, Leidal et al. [95] successfully loaded RNA-binding proteins into EVs via LC3-conjugation machinery.

Genetic materials

Natural EVs can carry both coding RNAs (mRNAs) and noncoding RNAs (long noncoding RNAs, miRNAs, and circular RNAs), which suggests outstanding ability in transferring diverse RNAs for therapeutic purposes [96]. Particularly, miRNAs in engineered EVs have been widely studied in kidney diseases. For example, BM-MSC-derived exosomes inhibited core fucosylation by delivering miR-34c-5p to reduce activation of pericytes, fibroblasts, macrophages, and renal interstitial fibrosis [74]. Furthermore, mRNAs loaded in EVs could be applied for personalized tumor vaccines [97] and the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic [98]. In addition, EVs loaded with small interfering RNA (siRNA) could also be a promising strategy to mediate gene silencing for cancer therapy [99]. Engineered red blood cell-derived EVs modified with peptide targeting KIM-1 have been constructed and successfully delivered siRNAs against P65 and Snai1 into injured kidneys. Dual inhibition of P65 and Snai1 expression significantly alleviated kidney inflammation and fibrosis in mouse models of IRI and UUO [75].

Conclusion and perspectives

In recent years, it has been shown that maladaptive repair of TECs, PTC rarefaction, activation and proliferation of myofibroblasts, diverse functions of macrophages, ECM hemostasis, and EV-mediated cellular communications are important in tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis. However, the accurate mechanism of renal fibrosis remains to be fully clarified. By combination and integration of single-cell and multiomics techniques, it is now possible to better understand disease mechanisms [100–102]. In addition, EV-mediated cellular communication also provides a new insight into the pathogenesis process of renal fibrosis.

Despite the development of therapeutic agents ranging from chemical compounds to gene therapies against renal fibrosis, clinical translation from bench to bedside is often limited due to the slow progression of disease and heterogeneity of patients as well as lack of noninvasive biomarkers for renal fibrosis [103]. Recent research showed that positron emission tomography imaging of collagen and molecular imaging of fibrosis may allow efficient, noninvasive, quantitative, and longitudinal results [104]. Urinary EVs released from intrinsic renal cells hold the potential to predict and monitor CKD progression as a “fluid biopsy” approach; for instance, miR-29 in urine EVs has been identified as a biomarker of renal fibrosis [105].

EV-based treatments are promising approaches to realize targeted therapy. However, clinical application of EVs in kidney disease is far from practical. Low production of EVs greatly hinders their clinical application, which encourages advances in stimulating EV shedding and production, but the properties and functions of EVs should be evaluated further. In addition, engineered EVs, including EVs from genetically engineered cells, post-modified EVs (drug loaded, surface modified), and EV-inspired liposomes have been developed to enhance therapeutic activity [106]. MSC-EVs and EVs from other sources have been tested for safety and efficacy in numerous ongoing clinical trials for diseases including diabetes, SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, Alzheimer’s disease, and various tumors [106]. Due to the heterogeneity of EVs, it is urgent to establish a good unified standard to achieve large-scale and efficient production of clinical-grade EVs for clinical application. Therapeutic EV production is a complex process in which minor changes can have significant impacts on product quality and efficacy [106]. Furthermore, administration route, dosage, and biological distribution of EVs in vivo should be considered before EV products are applied in patients. The underlying mechanisms of EV production, secretion, and uptake are not fully clarified at present. Robust studies of basic EV biology are needed to enable clinical translation. Emerging advanced technologies such as super resolution microscopy, single extracellular vesicle assay, and nanoflow cytometry could be useful tools to achieve deep understanding of EV biology [107].

Overall, with progress in understanding the mechanisms of renal fibrosis as well as the emerging therapeutic strategies, particularly EV-based therapies, we look forward to a new era of precise and targeted treatments for renal fibrosis.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This study is supported by grants from the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (grant No. 82122011, 81970616, and 82241045).

Data sharing statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: CW, SWL, LLL

Funding acquisition, Supervision: BCL, LLL

Writing–original draft: CW, SWL

Writing–review & editing: All authors

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.