Introduction

Cholesterol embolization (CE) is a potentially serious manifestation of systemic atherosclerosis associated with high morbidity and mortality. Although CE can occur spontaneously, it is recognized as an iatrogenic complication of an invasive vascular procedure, such as manipulation of the aorta during angioplasty or vascular surgery, or after anticoagulation and fibrinolytic therapy [1]. The clinical manifestation of CE is characterized by a shower of microemboli, leading to the occlusion of small vessels and associated inflammatory responses in a variety of organs including the kidney, skin, brain, gastrointestinal tract, and the extremities [1], [2], [3], [4]. The frequency of skin findings in CE is high, ranging from 35% to 96% [3]. In the lower extremities, CE may lead to a sudden development of purple or blue toes and discoloration of other regions of the foot. Because of the frequent occurrence of blue toes in association with CE, the term blue toe syndrome is occasionally used as a synonym for CE syndrome. However, specific treatment has not been established. Current treatment consists mainly of supportive care and secondary prophylaxis against further episodes of CE.

Herein, we report a case of spontaneously presenting blue toe syndrome caused by CE and accompanied by acute renal failure, in which lumbar sympathectomy relieved toe pain significantly and improved local blood flow in the ischemic lower extremities.

Case report

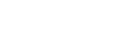

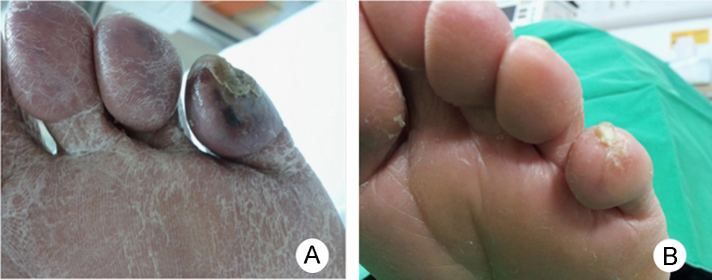

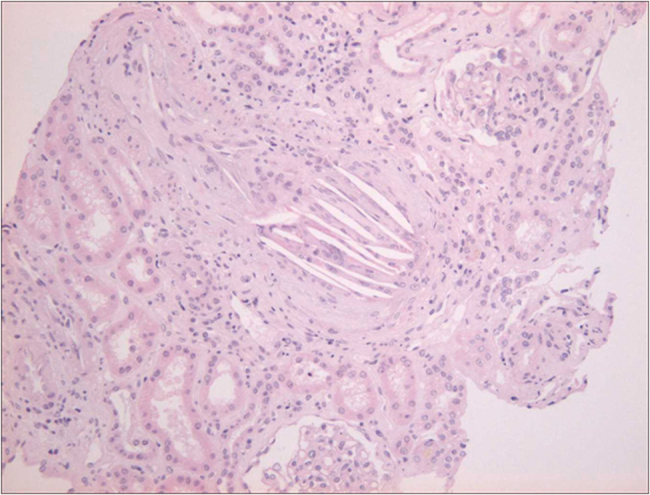

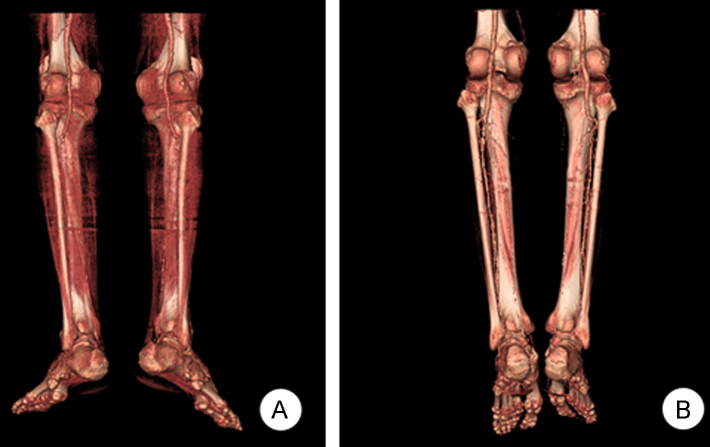

A 76-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for examination and treatment of a painful ulcer on the left fifth toe (Fig. 1A). He was a 75 pack-year smoker and had hypertension, dyslipidemia, and chronic kidney disease. On admission, his blood pressure was 200/100┬ĀmmHg. He presented with a blue and purple discoloration of his toe and weak pedal arterial pulses. The white blood cell count was 14,000/┬ĄL with 2.2% eosinophil concentration, with increases in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level. Serum creatinine level increased from 2.7 to 6.5┬Āmg/dL within 1 month. Urinalysis demonstrated 1+ proteinuria, and one red and one white cell per high-power field. Tests for antinuclear antibody, anti-DNA antibody, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative. The C3 level was decreased slightly. A renal ultrasound with Doppler showed both kidneys to have normal size and blood flow. The fundoscopic examination revealed no evidence of cholesterol emboli. Because of unexplained renal failure in the absence of any recent CE-associated vascular procedure or anticoagulation therapy, a kidney biopsy was performed subsequently to identify any treatable causes of acute kidney injury. The biopsy demonstrated an interlobular renal artery occluded by atheromatous material with a characteristic needle-shaped cholesterol cleft (Fig. 2). The patient's renal function deteriorated further and hemodialysis was initiated. His toe ulcer progressed to gangrene with ischemic pain, which was unresponsive to narcotics and prostaglandin therapy. Computed tomography (CT) angiography showed extensive atherosclerotic calcified plaques with thrombus, mild aneurysmal dilatation of the abdominal aorta, and total, bilateral occlusion of the tibial and peroneal arteries (Fig. 3A). We could not consider surgical or endovascular therapy because of the poor general condition of the patient and a risk of repeated embolism. Instead, we chose lumbar sympathectomy as a pain-relieving procedure. An anesthesiologist performed percutaneous chemical lumbar sympathectomy with 8┬ĀmL of 99% ethanol at the L2ŌĆōL3 level under fluoroscopic guidance. Shortly after alcohol sympathetic neurolysis, the patient's systolic blood pressure dropped transiently to 70┬ĀmmHg but stabilized immediately with normal saline administration alone. Following sympathectomy, toe pain was relieved dramatically with an improvement in Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score to three points, from a previous eight points. The gangrenous lesion, which was considered for amputation previously also healed (Fig. 1B). In fact, he could walk without pain. Subsequent CT angiography showed improvement in blood flow in the ischemic lower extremities (Fig. 3B). Renal function did not recover, and the patient was transferred to a chronic dialysis program. One year since, the ischemic toe pain has not recurred.

Discussion

Blue toe syndrome is a frequent and serious cutaneous manifestation of tissue ischemia and is caused by CE. Furthermore, the highest rates of cutaneous involvement have been reported in patients with a concomitant renal manifestation of CE [3]. If microvascular ischemia is severe, tissue necrosis may develop, ranging in severity from small superficial ulcerations to gangrene, thus leading to amputation [5]. Since cholesterol emboli occlude smaller arteries and arterioles rather than superficial large palpable arteries, many patients presenting with disabling blue toe syndrome may not be candidates for direct arterial intervention. Moreover, many reports suggest that such an arterial intervention can induce secondary CE and contrast nephrotoxicity, further aggravating renal function [6]. Surgery (endarterectomy or bypass with exclusion of the source of emboli) can be a treatment option; however, it is rarely indicated because the origin of cholesterol crystal embolization is often not certain. Moreover, many patients have a poor physical condition with a serious cardiovascular disease or renal dysfunction. Therefore, these patients may not tolerate the surgery, which is itself associated with substantially high morbidity and mortality [1]. These factors were also true for our patient. In our case, the patient experienced medically intractable ischemic pain and secondary infection of a gangrenous toe. Therefore, toe amputation was the only reasonable choice. In this situation, lumbar sympathectomy markedly improved wound healing as well as ischemic pain by increasing blood flow to the ischemic area, leading to ŌĆ£limb salvage.ŌĆØ

Prior to the era of direct arterial surgery, lumbar sympathectomy was performed in virtually all forms and stages of peripheral vascular occlusive disease, Buerger's disease, and some vasospastic disorders. A benefit of sympathectomy is explained as its circulatory effect by diminishing vasoconstrictor tone, thereby increasing blood flow to the ischemic area. In addition, an analgesic effect is produced by the interruption of sympatheticŌĆōnociceptive coupling and by direct neurolytic action on nociceptive fibers [7], [8]. With the advent of direct arterial manipulation, lumbar sympathectomy is considered old fashioned and an adjunctive treatment for limb salvage in patients with unreconstructable peripheral vascular disease [7], [9], [10]. Moreover, consistency and long-term effectiveness of sympathectomy are debatable. Some clinicians consider it to be of very little value in current practice. However, as shown in our case, no demonstrable efficacious treatment exists for blue toe syndrome secondary to CE, and any therapeutic approach that may be of benefit deserves consideration. In this situation, lumbar sympathectomy may be worthy of consideration as a valuable, alternative treatment option.

Both randomized controlled and cohort studies have been conducted to investigate symptom control and long-term benefits of lumbar sympathectomy, but many have failed to identify objective benefits. Nevertheless, multiple studies have shown consistent symptom control in many patients with critical limb ischemia, in which patient selection has been found to play a major role [11], [12], [13]. In other words, the effect of sympathectomy remains controversial probably because of a lack of a standard method of patient selection. Although there is no definitive preprocedural measure to predict outcomes for sympathectomy, many reports suggest that sympathectomy may be ineffective in the presence of extensive tissue necrosis far beyond gangrene of individual toes or in the presence of an ankle brachial pressure index of Ōēż0.3 [7], [8], [9], [10]. Also, diabetic patients are generally perceived to have little response to sympathectomy because they are often autosympathectomized. However, the primary effect of lumbar sympathectomy is based on the abolition of increased vasomotor tone, and such tone can be expected to be normal in great majority of diabetic patients, even in severe diabetic neuropathy [14]. Therefore, vasomotor reactivity tests can be helpful in determining whether or not to perform sympathectomy in patients with diabetes mellitus. We assume that these prognostic markers obtained through the above tests can also be useful for patient selection and indication of lumbar sympathectomy in blue toe syndrome caused by CE. Unfortunately, in our case, the ankle brachial pressure index test, which might provide objective data regarding limb circulation and collateral vessels available to respond to sympathectomy, was not performed.

Although large, randomized controlled studies with long-term follow-up examination periods are needed, Lee et al [10] performed a retrospective review of 45 patients with toe gangrene that were considered unamenable to direct arterial surgery and were thus managed by lumbar sympathectomy alone. At the 5- and 8-year follow-up examination, cumulative limb salvage was 71% and cumulative toe salvage 51%, indicating a possibility that the effect of sympathectomy can be durable. Moreover, chemical lumbar sympathectomy is a relatively inexpensive, minimally invasive, and safe procedure, with a low incidence of significant morbidity [8], [9]. Adverse events associated with lumbar sympathectomy have been reported to be temporary in most cases, and major complications are infrequent. Complications include neurological, renal and ureteric, vascular, and other miscellaneous concerns. Genitofemoral neuralgia is the commonest complication of lumbar sympathectomy, with an incidence of approximately 5ŌĆō10%. However, the duration rarely exceeds 2ŌĆō6 weeks, and symptoms usually tend to regress spontaneously or can be relieved by simple analgesics. Failure of ejaculation may follow sympathectomy if the first lumbar ganglion is ablated, and this occurs more commonly after bilateral procedures. Subarachnoid injection, epidural injection, aseptic meningitis, and paraplegia have been reported very rarely. Penetration of the kidney, its capsule, or the ureter can occur, and the use of fluoroscopic guidance or CT can reduce these complications greatly. Vascular complications include possible penetration of inferior vena cava, injury of arteries, and hypotension. Retroperitoneal hematoma formation has been described in anti-coagulated patients. Other miscellaneous complications that have been reported include allergic reactions to contrast media and injury of the intervertebral disc without adverse consequences [9], [15]. Sympathectomy may therefore be justified in patients at risk of limb loss for which surgical reconstruction or angioplasty is not possible, in the hope that a few selected proportion may benefit, even if the benefit proves to be temporary.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of blue toe syndrome treated via sympathectomy in a patient with acute renal failure caused by CE, although several therapeutic approaches such as prostaglandin analogue, corticosteroid therapy, and statin use have been attempted with or without success in similar situations [6]. Lumbar sympathectomy may be a valuable alternative therapeutic modality in properly selected patients experiencing intractable, progressive ischemic toe disease, unamenable to other treatments and caused by CE. Larger clinical trials are needed to confirm our observations.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print