Fabry disease exacerbates renal interstitial fibrosis after unilateral ureteral obstruction via impaired autophagy and enhanced apoptosis

Article information

Abstract

Background

Fabry disease is a rare X-linked genetic lysosomal disorder caused by mutations in the GLA gene encoding alpha-galactosidase A. Despite some data showing that profibrotic and proinflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress could be involved in Fabry disease-related renal injury, the pathogenic link between metabolic derangement within cells and renal injury remains unclear.

Methods

Renal fibrosis was triggered by unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) in mice with Fabry disease to investigate the pathogenic mechanism leading to fibrosis in diseased kidneys.

Results

Compared to kidneys of wild-type mice, lamellar inclusion bodies were recognized in proximal tubules of mice with Fabry disease. Sirius red and trichrome staining revealed significantly increased fibrosis in all UUO kidneys, though it was more prominent in obstructed Fabry kidneys. Renal messenger RNA levels of inflammatory cytokines and profibrotic factors were increased in all UUO kidneys compared to sham-operated kidneys but were not significantly different between UUO control and UUO Fabry mice. Protein levels of Nox2, Nox4, NQO1, catalase, SOD1, SOD2, and Nrf2 were not significantly different between UUO control and UUO Fabry kidneys, while the protein contents of LC3-II and LC3-I and expression of Beclin1 were significantly decreased in UUO kidneys of Fabry disease mouse models compared with wild-type mice. Notably, TUNEL-positive cells were elevated in obstructed kidneys of Fabry disease mice compared to wild-type control and UUO mice.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that impaired autophagy and enhanced apoptosis are probable mechanisms involved in enhanced renal fibrosis under the stimulus of UUO in Fabry disease.

Introduction

Fabry disease (OMIM #301500) is a rare X-linked lysosomal storage disorder resulting from an error in glycosphingolipid metabolism caused by a lack of alpha-galactosidase A (α-Gal A) [1,2]. Deficiency of α-Gal A can cause progressive accumulation of glycosphingolipids such as globotriaosylceramide (Gb3, also known as CD77 or GL3) in lysosomes. Clinical manifestations of Fabry disease are consequences of such Gb3 accumulation in various tissues and organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, and kidney [1,3]. Renal involvement is observed in approximately 55% of patients with Fabry disease [4]. In males with the classical form of Fabry disease, renal manifestation can start with microalbuminuria in infancy. Disease manifestation becomes evident with higher albuminuria and overt proteinuria in childhood and early adulthood [3,5]. In later adulthood, around the third or fourth decade of life, the glomerular function begins to be affected, leading to chronic kidney disease and ultimately end-stage kidney disease within the fifth decade [3]. It is difficult to recognize prodromal Fabry disease due to its highly variable and nonspecific phenotype, and low prevalence rate. Many patients are diagnosed late or never. This remains an unsolved problem [6]. Commercially approved enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) and pharmacological chaperones are available to treat Fabry disease.

Despite marked advances in patient care and improved overall outlook on Fabry disease [5], current therapeutic strategies are insufficient to stop or reverse most processes of Fabry disease. There is a significant need to develop other therapeutic approaches based on an increased understanding of Fabry disease beyond the primary enzyme deficiency [7]. The exact mechanism through which the disease can cause multisystemic damage is poorly understood. High levels of glycolipids in cells and plasma affected by Fabry disease are insufficient to explain the pathophysiology of this disease and the inter- or infrafamilial phenotype variability in patients with the same GLA mutations [8]. Researchers have suggested that abnormal accumulation of Gb3 or globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3) due to α-Gal A deficiency could trigger different cellular mechanisms and affect phenotypic expression of Fabry disease [8,9]. Lysosomal deposits can act in a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP), known to represent endogenous molecules released from injured or dying cells [8]. In addition, intracellular accumulation of substrates could cause DAMP production by injured cells with subsequent proinflammatory activity such as increased recruitment of cytokines, proinflammatory factors, and leukocyte activity [8,10]. Indeed, most studies have emphasized the role of inflammation in tissue damage in Fabry disease [1,7,11]. Previous studies have shown that increased oxidative stress and altered antioxidant defenses could be involved in the vasculopathy of Fabry disease [7,12]. Altered nitric oxide generation and increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrotyrosine have been observed in patients and animal models of Fabry disease [13–15]. Another study has shown that decreased level of tetrahydrobiopterin, an essential cofactor for the normal enzymatic function of all isoforms of nitric oxide synthase and aromatic amino acid hydroxylases, in Fabry mouse tissues contributes to disease pathogenesis through oxidative stress, associated with antioxidant capacity of cells and uncoupling of nitric oxide synthase [13]. Expectedly, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), a regulatory cytokine with key functions under inflammatory and oxidative stress conditions, could promote fibrosis by enhancing the synthesis of extracellular matrix in cells and tissues of patients with Fabry disease via epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [8,16,17].

The autophagy-lysosome pathway could be another important signaling pathway contributing to the onset and progression of Fabry disease in involved cells and tissues [18]. A few investigations have suggested that dysregulation of autophagy resulting from Gb3 deposition could contribute to tissue damage [7,8,18]. A previous study has revealed that expression of microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3), a marker of autophagic vacuoles, is increased substantially in brains with α-Gal A deficiency in a mouse model of Fabry disease [18]. However, a connection between altered autophagy and renal involvement has yet to be established in Fabry nephropathy. The objective of this study was to examine how kidneys would respond and react to proinflammatory and profibrotic stimuli triggered by unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) in a mouse model of Fabry disease and to determine which pathophysiological signaling pathways are most altered in such kidneys.

Methods

Experimental animals

Fabry disease mice, a rodent model with α-Gal A gene-disruption, were bred to produce sufficient numbers. Heterozygous female mice were bred with control males to maintain the mouse colony. Mating between mutant males and females was performed to generate littermates with α-Gal A deficiency [18]. All mice were fed a rodent diet and water ad libitum. For this study, male Fabry disease mice or wild-type mice weighing 20 to 25 g underwent left ureteral ligation with 4-0 silk thread under isoflurane anesthesia. Sham operations were similarly performed for wild-type mice without ligation as described previously [19]. Mice were divided into three groups (n = 4 or 5 mice per group): sham-operated wild-type mice (Sham), UUO-operated wild-type control mice (UUO Cont), and UUO-operated Fabry disease mice (UUO Fabry). At 7 days after sham operation or UUO, mice were euthanized by exsanguination under isoflurane anesthesia, followed by trans-cardiac perfusion with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Sham-operated or obstructed kidneys were harvested for histological evaluation and molecular analysis. All experiments were performed following protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Catholic University of Korea Yeouido St. Mary’s Hospital (No. YEO-2020-009FA).

Genotyping

To genotype each mouse, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed as described previously [16] using the following primers: Exon3-forward: 5’-GCAACTGTTCATGCAGATGG-3’; Exon3-reverse: 5’-CTGCGCATCAATGTCATAGG-3’; Neo-forward: 5’-GAAGGGACTGGCTGCTATTG-3’; Neo-reverse: 5’-AATATCACGGGTAGCCAACG-3’. Results were used to indicate which mice were wild-type or α-Gal A deficient (Supplementary Fig. 1, available online).

Histology

To evaluate the severity of tubulointerstitial fibrosis, 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde-fixed kidney sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome or with sirius red following the manufacturer’s protocols (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) [20]. More than 20 fields were randomly selected for quantitative evaluation and analyzed in a blinded manner using ImageJ 1.53a software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

According to the manufacturer's manual, total renal RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Quantitative reverse transcription (qRT) PCR assays were performed using SYBR Premix (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan). Primer sequences for each gene used in PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 1 (available online). The specificity of PCR was confirmed by analyzing the melting curve. All PCR assays were performed in duplicate. Results were normalized to messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in the sham-operated kidney tissues of wild-type mice.

Immunoblotting

Total proteins from harvested kidneys were extracted using a PRO-PREP Protein Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea). Protein concentrations were determined using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). After electrophoresis, proteins in gels were transferred into nitrocellulose membranes and incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Antibodies against the following proteins were used: NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), catalase (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1; Enzo Life Science, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA), SOD2 (Abcam), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1; Thermo Fisher Scientific), nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), Nox2 (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA), Nox4 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), LC3B (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), Beclin1 (Novus), β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), β-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Sigma-Aldrich). After washing with PBS, all blots were incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. Immunoreactive proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence reagents. Densities of protein bands were measured and normalized to those of respective housekeeping proteins in the same sample.

Transmission electron microscopy

For electron microscopic examination, small sections of kidney tissues were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer. After washing and dehydrating in serial alcohol and propylene oxide, tissues were infiltrated with a series of graded ethyl alcohol solutions and embedded in Epon substitute. Thin sections were prepared and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Samples were observed under a transmission microscope to identify representative lesions in glomeruli and proximal tubules.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling assay

To examine DNA fragmentation indicative of apoptosis, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. TUNEL-positive cells were evaluated in 20 randomly selected fields for each section using ImageJ 1.53a software.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software LLC, La Jolla, CA, USA). In all analyses, p-values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Fabry disease aggravates renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis triggered by unilateral ureteral obstruction

Compared with sham-operated kidneys, obstructed kidneys induced by UUO showed renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis, as indicated by Masson’s trichrome and sirius red staining (Fig. 1). Besides, UUO-induced renal fibrotic areas were larger in UUO kidneys of Fabry disease mice than in sham-operated kidneys.

Increased fibrosis in obstructed kidneys of Fabry disease mice.

Representative micrographs after Masson’s trichrome (A) and sirius red (B) staining for kidneys from different groups (×200 in all micrographs). (C) Quantitative analysis for Masson’s trichrome staining showing significantly aggravated fibrotic lesions by unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) with greater enhancement in Fabry disease mice (*p = 0.001 vs. Sham, **p < 0.001 vs. Sham, p = 0.006 vs. UUO Cont). (D) More enhanced renal fibrotic areas in obstructed kidneys of Fabry disease mice as indicated by sirius red staining (*p = 0.009 vs. Sham, **p < 0.001 vs. Sham, p = 0.02 vs. UUO Cont).

Cont, control; Sham, sham-operated wild-type mice.

Fabry disease has no further effect on inflammation or epithelial-mesenchymal transition triggered by unilateral ureteral obstruction

Results of qRT-PCR revealed that renal mRNA levels of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) were significantly increased on day 7 post-UUO compared to those of sham-operated kidneys (Fig. 2A–C). However, there was no additional increase in the mRNA levels of inflammatory cytokines in obstructed kidneys of Fabry disease.

Renal messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels of genes involved in inflammation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

(A) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis showing the increased expression level of renal interleukin (IL)-1β on day 7 after unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO), without significant difference between UUO control (Cont) and UUO Fabry (*p = 0.05 vs. Sham, **p = 0.02 vs. Sham). (B) Increased IL-6 mRNA level in UUO kidneys (*p = 0.02 vs. Sham, **p = 0.04 vs. Sham). (C) Similarly increased tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) mRNA level in both UUO Cont and UUO Fabry (*p = 0.05 vs. Sham, **p = 0.05 vs. Sham). (D) Significantly enhanced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)2 mRNA level in the obstructed kidneys of all UUO groups (*p = 0.03 vs. Sham, **p = 0.04 vs. Sham). (E) Increased renal MMP9 mRNA level observed in all UUO groups (*p = 0.01 vs. Sham, **p = 0.02 vs. Sham). (F) No significant increase in epithelial cadherin (E-cadherin) mRNA level in all UUO groups compared to Sham. (G) Significantly increased renal mRNA level of vascular E-cadherin (VE-cadherin) in UUO Cont (*p = 0.03 vs. Sham). (H) Significantly enhanced renal α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) mRNA level in UUO Cont (*p = 0.009 vs. Sham). (I) Increased fibronectin mRNA level in all UUO groups (*p = 0.006 vs. Sham, **p = 0.05 vs. Sham). (J) Increased renal vimentin mRNA level in all UUO groups (*p = 0.002 vs. Sham, **p = 0.004 vs. Sham). (K) Similarly enhanced mRNA level of renal transforming growth factor (TGF)-β in all UUO groups (*p = 0.01 vs. Sham, **p = 0.007 vs. Sham). (L) Increased collagen type IVα1 chain (COL4A1) mRNA level on day 7 after UUO in obstructed kidneys of all UUO groups (*p = 0.004 vs. Sham, **p = 0.04 vs. Sham).

Sham, sham-operated wild-type mice.

Levels of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)2 and MMP9 mRNA were significantly enhanced in obstructed kidneys of both UUO control and UUO Fabry mice without significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 2D, E). There was no significant difference in epithelial cadherin (E-cadherin) mRNA level among groups (Fig. 2F). Renal mRNA levels of vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) were significantly enhanced in UUO control mice compared to sham-operated mice and tended to be increased in UUO Fabry mice, without statistical significance (Fig. 2G, H). Fibronectin, vimentin, TGF-β1, and collagen type IVα1 chain (COL4A1) mRNA levels were increased at day 7 after UUO in both UUO control and UUO Fabry without a significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 2I–L). Collectively, the expression of inflammation or EMT-related genes was significantly increased by a similar amount in obstructed kidneys of both wild-type and Fabry mice, suggesting that Fabry disease had no additional effect on renal inflammation or EMT stimulated by UUO surgery.

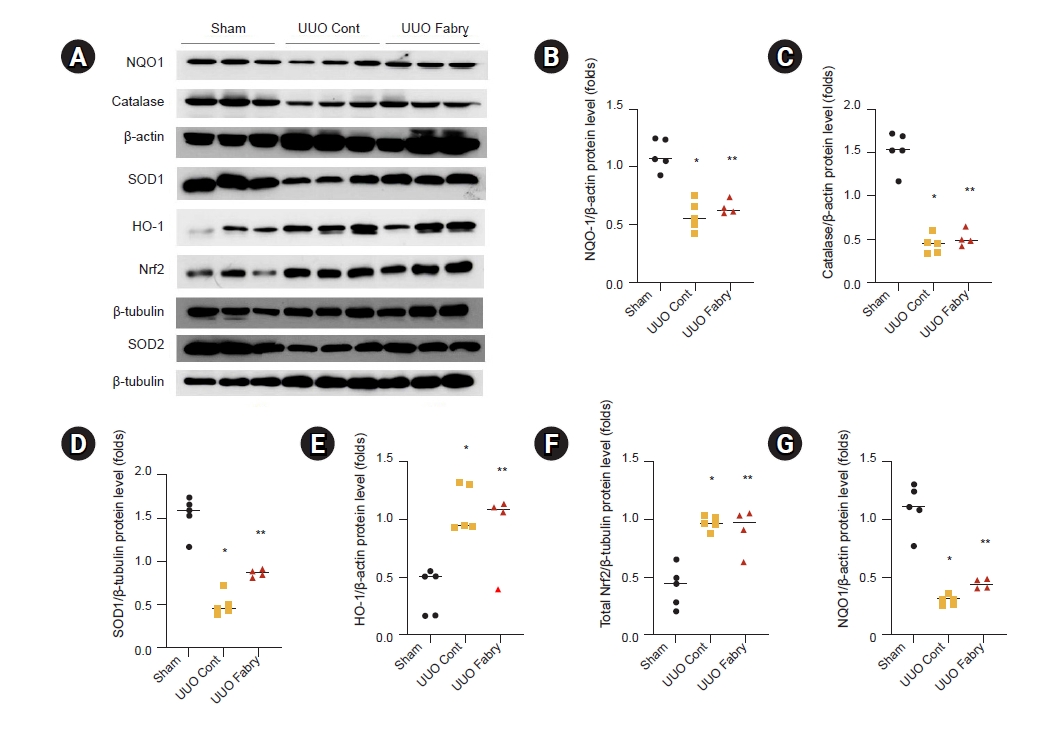

Obstructed kidneys of Fabry disease mice have similar renal antioxidant enzyme and oxidative stress status

On day 7 post-UUO, obstructed kidneys showed suppressed expression of NQO1, catalase, SOD1, and SOD2 proteins (Fig. 3A–D, G). However, Fabry disease did not confer further suppression of those antioxidant enzymes. Rather, renal SOD1 expression in UUO Fabry was slightly higher than that of UUO Cont but still significantly lower than that of Sham Cont (Fig. 3A, D). By contrast, protein expression levels of HO-1 and Nrf2, a transcription factor involved in the induction of cytoprotective antioxidants, were similarly increased by UUO in both wild-type and Fabry disease mice (Fig. 3A, E, F).

Effect of Fabry disease on antioxidant enzymes in unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) kidneys.

(A) Representative western blot results for NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), catalase, superoxide dismutase (SOD)-1, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), total nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), and SOD2. (B) Increased renal protein expression of NQO1 after UUO in both wild-type and Fabry disease mice, without significant difference between the two UUO groups (*p < 0.001 vs. Sham, **p < 0.001 vs. Sham). (C) Similarly increased catalase expression after UUO in UUO control (Cont) and UUO Fabry (*p < 0.001 vs. Sham, **p < 0.001 vs. Sham). (D) Decreased expression of SOD1 in both UUO Cont and UUO Fabry groups, with UUO Fabry having a slightly higher level than UUO Cont (*p < 0.001 vs. Sham, **p < 0.001 vs. Sham, p = 0.02 vs. UUO Cont). (E) Renal HO-1 expression significantly increased in all UUO groups (*p = 0.003 vs. Sham, **p = 0.02 vs. Sham). (F) Significantly enhanced total Nrf2 expression in all UUO groups (*p < 0.001 vs. Sham, **p = 0.002 vs. Sham). (G) Lower renal SOD2 expression in both UUO Cont and UUO Fabry than in Sham (*p < 0.001 vs. Sham, **p <0.001 vs. Sham).

Sham, sham-operated wild-type mice.

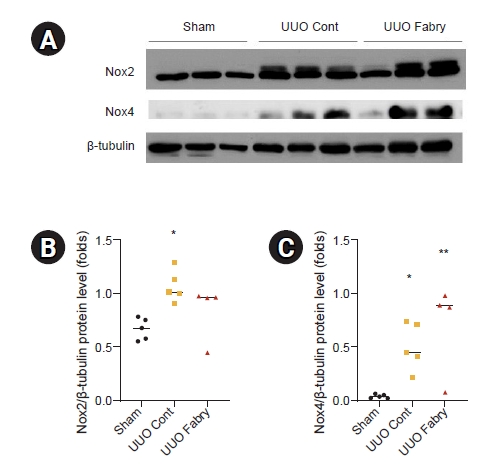

Results of Western blot analysis revealed that protein level of Nox2, one of the NADPH oxidases in the Nox family, was significantly increased in UUO control and tended to be increased in UUO Fabry without a statistically significant difference from that of the sham group (Fig. 4A, B). Renal Nox4 expression level was significantly increased in all UUO groups compared to that in the sham group (Fig. 4A, C). These results demonstrate that Fabry disease mice experience no further aggravation of antioxidant enzymes or oxidative stress in obstructive nephropathy compared to wild-type.

Effect of Fabry disease on oxidative stress in unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) kidneys.

(A) Representative western blot results for Nox2 and Nox4. The β-tubulin image was reused because the membrane for immunoblot analyses of superoxide dismutase-1, heme oxygenase-1, and total nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related factor 2 in Fig. 3 was reprobed with anti-Nox2 and anti-Nox4. (B) Renal Nox2 expression was significantly increased in UUO control (Cont) compared to Sham. Nox2 level in UUO Fabry was not significantly different from that in Sham or UUO Cont (*p = 0.02 vs. Sham). (C) Both UUO Cont and UUO Fabry had a significant increase in Nox4 level in obstructed kidneys (*p < 0.046 vs. Sham, **p = 0.008 vs. Sham).

Sham, sham-operated wild-type mice.

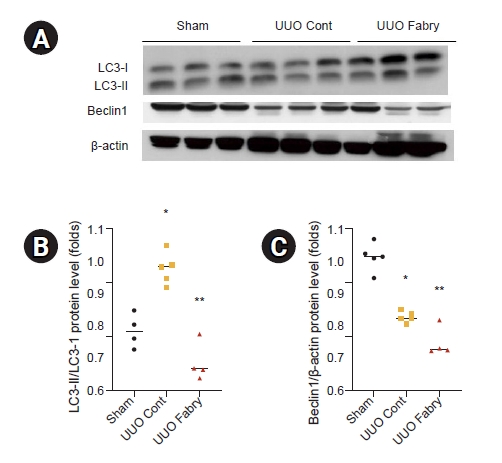

Fabry disease mice show altered autophagy in unilateral ureteral obstruction kidneys

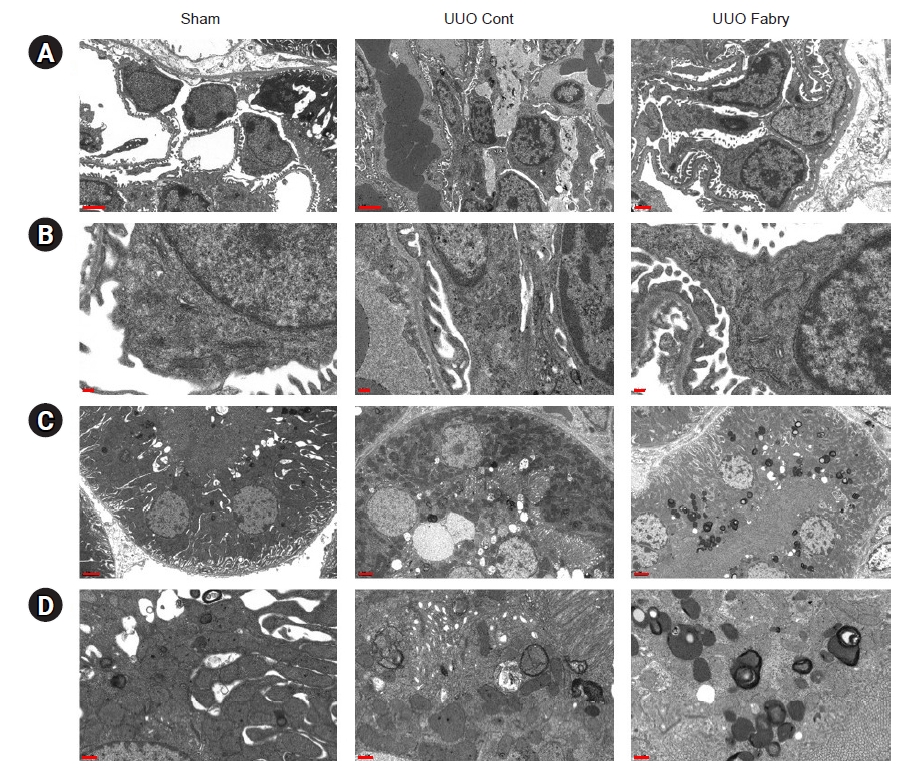

It has been reported that autophagy is involved in the development and progression of renal fibrosis induced by UUO [21,22]. The ratio of LC3-II to LC3-I, a reliable marker of autophagy, was significantly increased in UUO control but decreased in UUO Fabry (Fig. 5A, B). In addition, renal expression of Beclin1, a protein involved in the initiation of autophagosome formation by forming a multiprotein complex [23], was significantly decreased in UUO control but further decreased in UUO Fabry (Fig. 5A, C). On electron microscopy, there were more autophagosomes and autophagic vesicles in proximal tubular cells of the UUO Cont group than in those of the Sham group (Fig. 6). However, definite autophagosomes were rarely recognized in obstructed kidneys of Fabry disease mice except prominent electron-dense inclusions. Taken together, these results indicated that autophagy was induced in UUO kidneys of wild-type mice but attenuated in those of Fabry disease mice.

Effect of Fabry disease on autophagy in unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) kidneys.

(A) Western blot results representing microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) and Beclin1. The β-actin image was reused because the membrane for immunoblot analysis of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 and catalase in Fig. 3 was reprobed with anti-LC3 and anti-Beclin1. (B) LC3-II/LC3-I level was increased in UUO control (Cont) but decreased in UUO Fabry (*p = 0.010 vs. Sham, **p < 0.001 vs. UUO Cont). (C) Renal expression of Beclin1 was lower in UUO Fabry than in Sham or UUO Cont (*p < 0.001 vs. Sham, **p < 0.001 vs. Sham, p = 0.03 vs. UUO Cont).

Sham, sham-operated wild-type mice.

Impaired autophagy in obstructed kidneys of Fabry disease mice.

Representative electron micrographs of glomeruli (A, B) and proximal tubules (C, D). (Sham A–D) Sham-operated alpha-galactosidase A wild-type mice had normal glomerulus and proximal tubule appearance. (Unilateral ureteral obstruction [UUO] control [Cont] A–D) Following UUO, disruption of glomerular and tubular barriers, irregular cytoplasmic processes, and autophagic vacuoles were shown. (UUO Fabry A–D) Inclusion bodies containing globotriaosylceramide were observed in renal proximal tubular cells but not in podocytes of UUO-operated Fabry disease mice.

Scale bars: 2 μm for A and C, 0.2 μm for B and D.

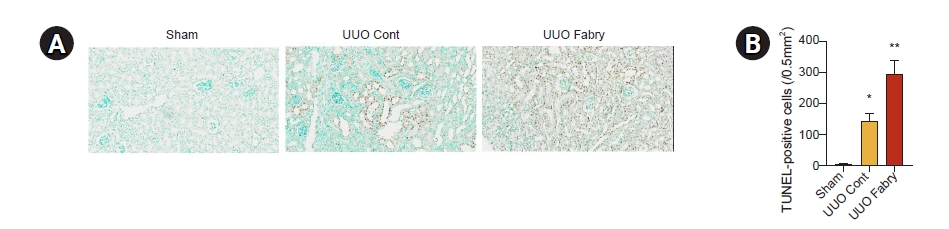

Fabry disease mice have a larger number of apoptotic tubular cells after unilateral ureteral obstruction

In TUNEL assay analyzing renal apoptosis, while a few TUNEL-positive cells were detected in sham-operated kidneys, there was a significant increase in the number of TUNEL-positive cells in UUO control (Fig. 7). Interestingly, the number of these apoptotic cells was increased further in UUO kidneys of Fabry disease mice, suggesting that Fabry disease is associated with enhanced tubular apoptosis in obstructed kidneys after UUO.

Increased apoptosis in obstructed kidneys of Fabry disease mice.

(A) Representative image of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (×200). (B) Quantification of renal TUNEL-positive cells showing increased apoptosis in wild-type mice with unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) and more highly enhanced apoptosis in Fabry disease mice with UUO (*p = 0.003 vs. Sham, **p < 0.001 vs. Sham, p = 0.002 vs. UUO control [Cont]).

Sham, sham-operated wild-type mice.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that UUO kidneys could induce renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis, inflammation, EMT, oxidative stress, autophagy, and apoptosis in similar patterns as described in previous reports [19,22,24]. In the setting of Fabry disease, a further increase in fibrosis without any change in levels of inflammation, EMT, antioxidant enzymes, or oxidative stress was observed in obstructed kidneys after UUO. These findings might be explained by altered autophagy and enhanced apoptosis in kidneys affected by Fabry disease.

Chronic immune system stimulation in Fabry disease has been reported [3]. Increase of inflammatory markers such as TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF receptor (TNFR) 1, TNFR2, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and soluble vascular adhesion molecule in patients with Fabry disease implicates chronic inflammation as a major driver of Fabry disease pathogenesis [25,26]. It has been suggested that glycolipids such as lyso-Gb3 bind to toll-like receptor 4, nuclear factor κB, and T lymphocytes, leading to chronic inflammation and associated vasculopathy [8]. However, another study has shown that treatment with only Gb3 could not induce an increased level of IL-1β, IL-6, or TNFα in an in vitro experiment using monocyte-derived dendritic cells and macrophages purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells [10]. Although there is limited research on Fabry disease-related inflammation in kidneys, TGF-β1, one of the key regulatory cytokines in many diseases, has been reported to play a role in renal pathogenesis in Fabry disease [16]. Upregulated TGF-β1 level appears to be associated with dysfunction of endothelial cells and podocytes affected by Fabry disease [16,27]. However, under renal injury induced by UUO in our experiment, Fabry disease mice did not show additional changes in proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, or TGF-β1 compared to wild-type mice. UUO in wild-type mice exerted the fibrotic response associated with EMT, as indicated by increased levels of MMP2, MMP9, VE-cadherin, α-SMA, fibronectin, vimentin, and COL4A1, consistent with previous reports [19,21]. However, the levels of these fibrotic factors were not higher in the obstructed kidneys of Fabry disease mice. Since TGF-β1 plays a role in the formation and proliferation of myofibroblasts [3], profibrotic cytokines and EMTs might have followed a similar pattern to the expression of TGF-β1.

Oxidative stress has been implicated as one of the major underlying mechanisms behind the pathogenesis of obstructive nephropathy [19,23]. Since mitochondria are the major source of ROS, mitochondria-rich proximal tubules appear to be the most susceptible to obstructive injury [23]. Increased ROS can also result from impaired antioxidant capacity [19]. Our study showed that the kidneys of UUO-operated mice had decreased levels of antioxidant enzymes, including NQO1, catalase, SOD1, and SOD2. Meanwhile, increased levels of renal HO-1 and Nrf2 proteins were noted on day 7 after UUO, suggesting that levels of these antioxidant proteins might not be enough to reverse the extensive renal injury induced by UUO. In Fabry disease, accumulated Gb3 has been suggested to be associated with oxidative stress [4]. However, our experiment's results rejected the initial hypothesis that Fabry disease would have more highly augmented oxidant stress and more impaired antioxidants under the stimulus of UUO. One representative finding is that the expression of Nox4, the major NADPH oxidase isoform expressed in mitochondrial fractions of the kidney, is increased in obstructed kidneys [23,28] but not further increased in obstructed kidneys affected by Fabry disease.

Since homeostatic processes are particularly active in renal proximal tubular cells, in which reabsorption and transport properties are the most active in the kidney, autophagy-mediated turnover of damaged mitochondria would be required for protecting proximal tubules from renal injury [29,30]. Considering that the lysosomal system captures and degrades worn-out intracellular constituents through autophagy, it is expected that altered autophagy could damage cells through defective mitochondrial clearance [30,31]. Like our study, numerous previous studies have reported that UUO can induce autophagy, as evidenced by increased LC3-II/LC3-I [32–34]. Autophagy has controversial roles in numerous diseases, including cancer, infection, neurodegeneration, aging, cardiovascular disease, and various kinds of kidney diseases [33,35]. Although autophagy could upregulate or downregulate the fibrotic process in different cell lines [32], pharmacological inhibition of autophagy or genetic attenuation of its activity can worsen renal fibrosis [32,33]. In the brain of α-Gal A-deficient mice, LC3 itself is substantially increased, while the expression of autophagosomes is relatively lacking, indicating induction of aberrant autophagy in Fabry disease [18]. Autophagic activity or flux is generally low under basal conditions but can be induced by various stimuli [33]. Our study results suggest that kidneys of Fabry disease mice could not respond appropriately to the need for autophagic activity.

Autophagy can interact with the apoptotic machinery by acting upstream of apoptosis, converging with the apoptotic pathway, or mediating steps downstream of apoptosis. Autophagy can prevent apoptosis by selectively removing damaged mitochondria that might otherwise accumulate under stress conditions [36]. A previous study has indicated that Beclin1 can regulate the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. In addition, Beclin1 can protect renal tubular epithelial cells from apoptosis after UUO [24]. Indeed, autophagy can degrade unnecessary or dysfunctional components and prevent cell apoptosis [37], and increased autophagy is observed alongside decreased apoptosis [38]. As some reports have demonstrated that inhibition of apoptosis could delay or reverse renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis [39], apoptosis might be an early event that precedes the onset of fibrosis [40]. According to our results, Fabry disease mice showed more severe renal fibrosis after UUO, but they did not show greater enhancement in inflammation, EMT, or oxidative stress in this rapidly progressive renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis mouse model. We speculate that the defective autophagic machinery in Fabry disease failed to upregulate autophagic activity in response to UUO stimuli, leading to renal apoptosis and subsequent fibrosis.

Although it has been suggested that ERT could slow the progression of renal involvement in Fabry disease, its limited effect in specific situations has been observed [5]. Considering that altered autophagy, a unique attribute of Fabry disease, might serve as one of the main mechanisms of renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis, findings from the current study indicate that autophagy is another therapeutic target in Fabry disease.

Supplementary Materials

Notes

Conflict of interest

Sungjin Chung is a deputy editor of Kidney Research and Clinical Practice and was not involved in the review process of this article. All authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This study was supported from The Catholic Medical Center Research Foundation 2019.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: SC, HSK

Data curation: SC, MS, YC, SO, ESK

Formal analysis: SC, YKK, SJS, SWP, SCJ, HSK

Funding acquisition: SC

Investigation: SC, MS, YC, SO, ESK

Writing–original draft: SC, HSK

Writing–review & editing: All authors

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jong Hee Chung (Department of Statistics, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea) for providing statistical advice.