| Kidney Res Clin Pract > Volume 35(1); 2016 > Article |

|

Abstract

Warfarin skin necrosis (WSN) is an infrequent complication of warfarin treatment and is characterized by painful ulcerative skin lesions that appear a few days after the start of warfarin treatment. Calciphylaxis also appears as painful skin lesions caused by tissue injury resulting from localized ischemia caused by calcification of small- to medium-sized vessels in patients with end-stage renal disease. We report on a patient who presented with painful skin ulcers on the lower extremities after the administration of warfarin after a valve operation. Calciphylaxis was considered first because of the host factors; eventually, the skin lesions were diagnosed as WSN by biopsy. The skin lesions improved after warfarin discontinuation and short-term steroid therapy. Most patients with end-stage renal disease have some form of cardiovascular disease and some require temporary or continual warfarin treatment. It is important to differentiate between WSN and calciphylaxis in patients with painful skin lesions.

Keywords

Calciphylaxis, End-stage renal disease, Warfarin skin necrosisWarfarin skin necrosis (WSN) is a nonhemorrhagic complication of warfarin treatment, and its prevalence is reported to be only 0.01‚Äď0.1% among patients taking warfarin [1]. Calciphylaxis is a rare, challenging complication of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) with a high mortality rate. WSN and calciphylaxis have common clinical features, and warfarin treatment is a representative risk factor for calciphylaxis [2]. We describe a patient undergoing peritoneal dialysis who exhibited painful ulcerative skin lesions after warfarin administration.

A 52-year-old man with aortic stenosis was admitted to the thoracic surgery department. He had undergone kidney transplantation 15 years previously but had been on peritoneal dialysis for the past 2 years because of graft failure. He was also diagnosed with secondary hyperparathyroidism accompanied by metastatic pulmonary calcification and had received ethanol injection to a right parathyroid nodule.

On hospital day (HD) 7, he underwent surgery to replace the aortic valve with a titanium-based prosthesis. During the operation, his aorta showed severe wall calcification. The final pathology finding of the original aortic valve was fibrocalcific valvulopathy. The day after the operation, warfarin was added to his medication lists without heparin overlapping. On HD 18, hemorrhagic pustules developed suddenly on both feet. The skin lesions were distributed over both feet and were accompanied by xerotic scale (Fig. 1). The lesions were tender. At that time, there was no change in his condition other than the skin lesions.

The patient's medications included renalmin (vitamin B and C complex), sevelamer, cinacalcet, and divalproex, all of which he had been taking before admission, and famotidine, atenolol, risperidone, isosorbide-5-mononitrate, Mypol (ibuprofen/codeine/acetaminophen complex), and warfarin, all of which were added after the surgery. During the hospitalization, serial assessment showed that C-reactive protein concentration was increasing, and intravenous vancomycin was added on HD 19. The initial differential diagnosis of the skin lesions was drug eruption and metastatic infection, and a skin biopsy and microbiology examination were performed. While waiting for the result, the skin lesions changed to necrotic ulcers accompanied by substantial pain and progressed to the thigh level of both legs.

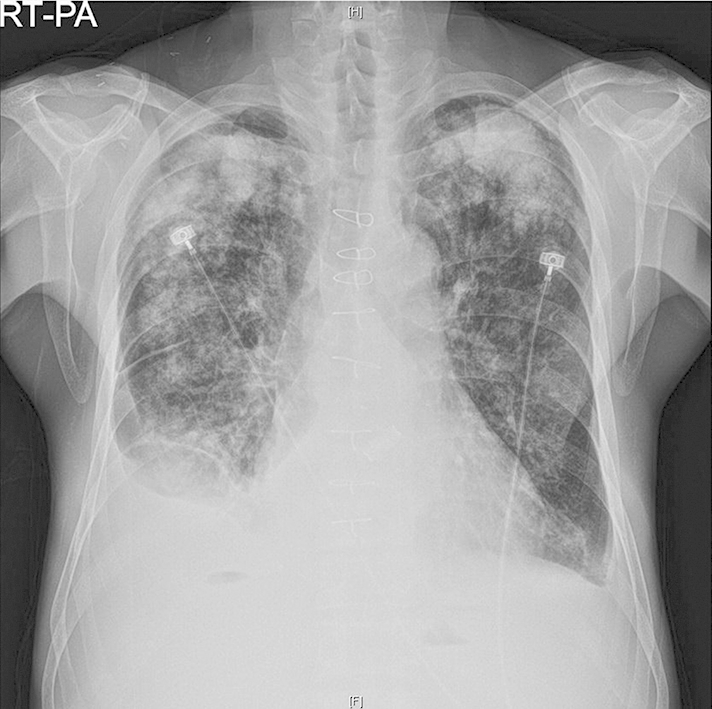

The patient was referred to the nephrology department because of painful skin lesions on HD 21. At that time, laboratory data showed a serum calcium of 8.7 mg/dL, phosphorus of 2.2 mg/dL, and intact parathyroid hormone level of 155.4 (reference range, 11.0‚Äď62.0) pg/mL. Chest radiographies showed extensive calcified consolidation in both upper lung fields (Fig.¬†2). We considered the possibility of calciphylaxis because his lungs and blood vessels showed extensive calcification and the host factors such as ESRD, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and recent warfarin commencement suggested the possibility of calciphylaxis. On HD 23, the pathology report indicated fibrinoid necrosis of entire dermal vessels, epidermal necrosis, and vesicles (Fig.¬†3A). Of note, no vascular calcification was detectable (Fig.¬†3B). Further review of the patient revealed no evidence of systemic vasculitis, and tests for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (antiproteinase 3¬†and antimyeloperoxidase) were negative.

On HD 27, we decided to withhold warfarin after consideration of WSN and started parenteral steroid (methylprednisolone 40 mg every 8 hours) after discussion with the allergy department. On HD 29, he was transferred to his local tertiary hospital for personal reasons. In that hospital, steroid therapy was continued and then tapered without the use of anticoagulants.

Twelve days after discharge, the patient visited our hospital because of epistaxis and was readmitted. At that time, the skin lesions had improved, and the steroid was tapered out. On HD 4 of the second hospitalization, we tried again to give the patient warfarin with enoxaparin. From HD 9 of the second hospitalization, painful skin lesions became aggravated. The reemergence of the painful skin lesions was strong evidence of WSN, and we immediately stopped the warfarin treatment and used short-term systemic steroid. The skin lesions and pain disappeared. We finally diagnosed the skin lesions as WSN, and enoxaparin was used as the anticoagulant. He was discharged after the systemic steroid was stopped and given enoxaparin as the maintenance anticoagulant.

WSN is an infrequent nonhemorrhagic complication of warfarin treatment. The first case was described in 1943, and the prevalence is reported to be 0.01‚Äď0.1% [1]. In Korea, 2 cases have been reported. One involved a 70-year-old man who presented with hemorrhagic bulla and ecchymosis on the right upper extremity that appeared after 6 days of warfarin treatment for acute stroke. He had no history of medical illness except hypertension [3]. The other case involved a 48-year-old woman who presented with skin necrosis on both breasts about 3 weeks after double valve replacement surgery and warfarin treatment. She also had no other significant medical history [4]. There are no reports of WSN in patients with ESRD. In patients with ESRD, WSN may be more challenging because of the need for an important differential diagnosis from calciphylaxis. When a patient with ESRD presents with painful skin lesions after warfarin treatment, the clinician should consider the possibility of the 2 main differential diagnoses‚ÄĒWSN versus calciphylaxis.

Although the pathogenesis is not fully understood, WSN results from the pharmacologic effects of warfarin. During the early phase of treatment, warfarin creates a paradoxically transient hypercoagulable state because several of the procoagulant and anticoagulant factors affected by warfarin have different half-lives. By contrast, calciphylaxis is a tissue injury caused by local ischemia resulting from metastatic calcification of vessels. Despite the different etiologies, the clinical manifestations of these distinct disease entities are similar, and it can be difficult to differentiate them based only on the clinical presentation. Both conditions can manifest initially as relatively mild skin lesions resembling an erythematous rash or livedo reticularis and then progress to skin ulcers or necrosis [1], [5]. Pain commonly accompanies the skin lesions. The skin lesions caused by WSN occur on the extremities, breasts, buttocks, and thighs, and the lesions caused by calciphylaxis occur on body areas with abundant adipose tissue [1], [6].

When treating this patient, some clinical findings made us consider both WSN and calciphylaxis. The patient exhibited painful skin lesions after warfarin administration, and these lesions progressed to necrotic ulcers. The patient's other conditions, such as ESRD, hyperparathyroidism, and history of metastatic calcification, led us to consider the diagnosis of calciphylaxis, for which warfarin is also a risk factor. Although the most painful sites were both thighs when we examined the patient on HD 24, the initial skin lesions were localized to the feet, which is not a typical location, and were accompanied by hemorrhagic pustules and xerotic scale, which we thought somewhat atypical.

We obtained definite clues from the histology findings. The main histopathology findings of WSN are diffuse microthrombi and fibrin deposits within the dermal and subcutaneous capillaries, venules, and deep veins, accompanied by endothelial cell damage [7]. By contrast, the typical findings of calciphylaxis are the presence of medial calcification and intimal proliferation of small- to medium-sized arteries, primarily in dermal and subcutaneous tissues [8]. In one review of a series of 16 patients with calciphylaxis, all the skin biopsy specimens showed small-vessel calcification regardless of the disease stage [5].

It is still controversial whether warfarin can be reintroduced safely in patients with WSN. A few literature have suggested that warfarin can be reattempted in combination with heparin and with a gradual (1 by 1 mg) increase of the warfarin dose [1], [9], [10]. It could also be applied for the preventive strategy for WSN. In particular, in patients with limited indication for lower molecular weight heparin or novel oral anticoagulant drug such as ESRD, reintroduction of warfarin rather than switch to other anticoagulant could be acceptable. However, reintroduction of warfarin aggravated the skin lesions despite the minimum dose of warfarin given with low-molecular-weight heparin in this patient. Considering the relatively rapid improvement after steroid use, we believe that hypersensitivity might contribute at least partly to the development of skin lesions.

It is important to differentiate between WSN and calciphylaxis because the medical management differs between these conditions [6]. The most important management of WSN is interruption of warfarin treatment and treatment with heparin, vitamin K, and protein C concentrate. When treating calciphylaxis, it is important to control calcium‚Äďphosphate metabolism, especially by stopping the use of calcium-based binders. Parathyroidectomy, sodium thiosulfate administration, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy are also options. The purpose of treatment is to avoid secondary skin infections, and adequate wound care and sometimes antibiotics are required. Both conditions may require surgical debridement if medical management fails.

This ESRD patient exhibited painful skin lesions after warfarin treatment commencement and had risk factors for calciphylaxis. We initially suspected calciphylaxis but diagnosed WSN based on the results of the skin biopsy. The skin lesions improved with discontinuation of warfarin and short-term use of systemic steroid. It is important for nephrologists to be aware of these 2 conditions and to quickly differentiate WSN from calciphylaxis to provide proper management of the patient.

References

1. Chan Y.C., Valenti D., Mansfield A.O., Stansby G.. Warfarin induced skin necrosis. Br J Surg 87:2000;266‚Äď272.

2. Wilmer W.A., Magro C.M.. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial 15:2002;172‚Äď186.

3. Ahn S.H., Choo I.S., Kim D.M., Lim G.H., Kim J.H., Kim H.W.. Warfarin induced skin necrosis. J¬†Korean Neurol Assoc 26:2008;142‚Äď145.

4. Moon S.C., Lee K., Lee H.J., Ahn D.H., Lim C.Y.. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis after valve surgery. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 32:1999;307‚Äď309.

5. Coates T., Kirkland G.S., Dymock R.B., Murphy B.F., Brealey J.K., Mathew T.H., Disney A.P.. Cutaneous necrosis from calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Am J Kidney Dis 32:1998;384‚Äď391.

6. Rockx M.A., Sood M.M.. A¬†necrotic skin lesion in a dialysis patient after the initiation of warfarin therapy: a difficult diagnosis. J¬†Thromb Thrombolysis 29:2010;130‚Äď133.

7. Nazarian R.M., Van Cott E.M., Zembowicz A., Duncan L.M.. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis. J¬†Am Acad Dermatol 61:2009;325‚Äď332.

8. Saifan C., Saad M., El-Charabaty E., El-Sayegh S.. Warfarin-induced calciphylaxis: a case report and review of literature. Int J Gen Med 6:2013;665‚Äď669.

Figure 1

Skin lesions on both feet. On HD 19, 11 days after the start of warfarin, erythematous pustules with tenderness developed suddenly on the lower aspects of both feet. The skin lesions expanded to the thigh level over the next few days.

HD, hospital day.

Figure 3

Pathologic findings of the skin. (A) Microscopic examination revealed intraepidermal vesicles (arrows) and multifocal necrosis of keratinocytes (arrowheads) with mixed inflammatory cell infiltration. Superficial dermis also shows diffuse infiltration of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and some eosinophils (hematoxylin and eosin, 100√ó). (B) Most of the small- and medium-sized dermal vessels showed extensive fibrinoid necrosis (arrows) and mixed inflammatory cell infiltration in the vascular wall and perivascular area. Calcification was not identified throughout the dermal vessels included in the specimen (hematoxylin and eosin, 400√ó).

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print