Introduction

Fabry nephropathy is caused by a deficiency in lysosomal alpha-galactosidase A (╬▒-Gal A), which leads to an accumulation of globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) in kidney cells and the increase of its metabolites including globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3) [

1]. Kidney involvement manifests as proteinuria and decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) values, both of which are indicative of chronic kidney disease [

2,

3]. Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) ameliorates Gb3 deposition in kidneys [

4,

5]. However, ERT has been shown to be ineffective in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (as indicated by proteinuria and a low GFR), emphasizing the need for early detection of Fabry nephropathy [

6ŌĆō

9]. A change in Gb3 deposition in a kidney biopsy is a useful indicator of Fabry nephropathy, but not of the efficacy of treatment [

10,

11]. Plasma lyso-Gb3, which has also been proposed as a diagnostic biomarker, has been shown to correlate with disease severity, enzyme replacement response, and phenotyping [

12,

13].

Fabry disease is classified as either a classical or variant phenotype (later-onset) [

14,

15]. Classical phenotypes present in childhood or adolescence with typical symptoms, including angiokeratomas, anhidrosis, tinnitus, hearing loss, corneal dystrophy, strokes, left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiac arrhythmias, abdominal discomfort, and diarrhea. In contrast, variant phenotypes have residual ╬▒-Gal A activity and are not associated with early manifestations of classic symptoms. Patients with the variant phenotype experience an essentially normal childhood and adolescence, typically only developing renal or cardiac disease in the third to seventh decades of life [

15].

The Korean medical insurance system and the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency maintain a rare-disease registry. Patients with Fabry disease are eligible for reimbursement of medical expenses if their diagnosis is confirmed. Despite these systems, individuals with variant phenotypic Fabry disease are commonly misdiagnosed and unable to receive treatment for an extended period of time due to a lack of typical symptoms; such patients are typically less seriously affected, and disease presentations may be limited to a single organ [

16]. Half of the patients with Fabry disease in a report from Argentina were diagnosed by nephrologists [

17].

Some patients with variant types who met the criteria for indication, which includes kidney manifestation, were covered by medical insurance for ERT. However, lyso-Gb3 was not covered by insurance in Korea [

18].

The pattern of Fabry nephropathy management in Fabry disease has not yet been surveyed in Korea. This study was designed to determine how Korean experts treat patients with Fabry nephropathy.

Methods

This study was approved by and received a waiver for the need for informed consent from the Institutional Review Board of the Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital (No. 2021-07-045-001).

A questionnaire to determine patterns in the diagnosis and treatment of Fabry nephropathy was distributed from 2021 to 2022. Questionnaires were emailed to and received by registered members of the Korean Society of Nephrology (KSN) and the Korean Society of Medical Genetics and Genomics (KSMG).

The questionnaire was divided into eight sections: 1) age group and sex of responder; 2) experience with Fabry disease, which includes yes/no questions in the past and present, and number and phenotype of patients; 3) timing of kidney biopsy (on diagnosis, before ERT, on a regular period, on time of proteinuria, or not necessary); 4) the need for a Fabry registry (yes vs. no); 5) check-up of lyso-Gb3 including the timing, interval, and needs for insurance coverage; 6) the interval and preferred tests for kidney function in Fabry disease; 7) the definition and tests of Fabry nephropathy; and 8) treatments other than ERT for Fabry nephropathy. Some detailed questions had multiple answers. The questionnaire is supplied in

Supplementary Table 1 (available online).

Descriptive analytical statistics were used to summarize survey responses. The chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables between groups. All statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 software program (IBM Corp.). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

In 1984, ophthalmologists reported the first case of Fabry disease in Korea. In 2019 and 2020, the number of newly registered patients according to the Korean Standard Classification of Disease (KCD) was 28 (8 male and 20 female) and 40 (16 male and 24 female), respectively [

17]. Despite the fact that the Korean medical insurance and Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency had a system for controlling rare diseases, Fabry disease patients were underdiagnosed and untreated for an extended period [

16,

19,

20]. Although Fabry disease has been diagnosed at an increasing rate in recent years, it is still extremely rare and difficult to access by experts [

21]. In a French survey of 152 nephrologists, few doctors (22%) directly managed patients with Fabry disease and 18% had made a diagnosis on their own [

21].

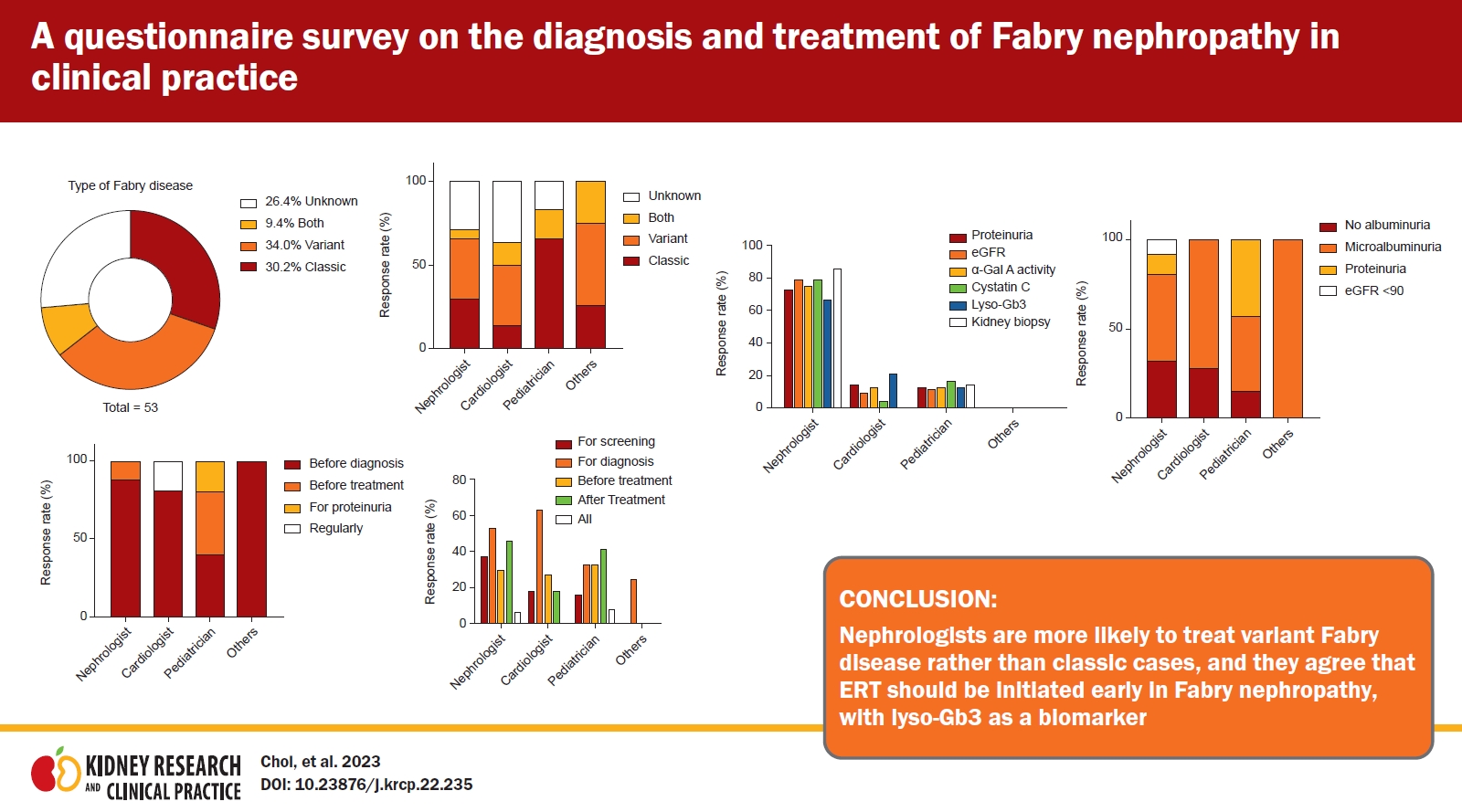

This study examines the current level of awareness among Korean specialists regarding available treatment options for Fabry nephropathy. The majority of respondents were nephrologists, while pediatricians and cardiologists followed in second and third place, respectively. Nephrologists in Argentina diagnosed half of Fabry disease patients [

22]. While nephrologists can also treat patients with classic diseases, they are more likely to treat variants of the disease [

23]. Different opinions were held by nephrologists and non-nephrologists regarding the diagnosis and treatment of Fabry nephropathy. Because it is a progressive multisystem disease, the involvement of other vital organs (the heart and brain, in particular) must be determined by an appropriate specialist [

24]. In addition, the clinical heterogeneity of Fabry disease necessitates an individualized approach to treatment that is based on the genotype, sex, family history, phenotype, and specific clinical symptom severity of each patient [

3,

6]. Confirming the opinions of experts about appropriate approaches to the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of Fabry nephropathy is therefore a useful activity.

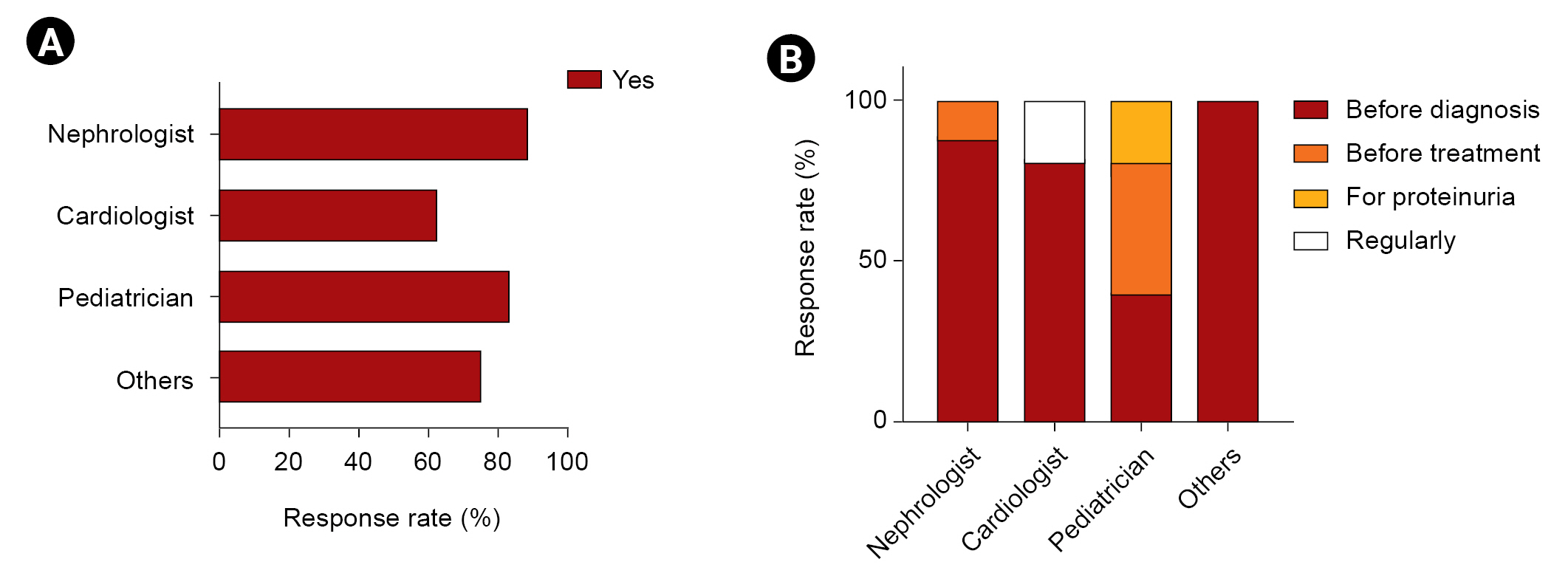

The majority of nephrologists considered the time of diagnosis optimal for a kidney biopsy, whereas 22.2% of non-nephrologists indicated that a kidney biopsy was unnecessary. Although there was no consensus on a definition of Fabry nephropathy, most respondents chose ╬▒-Gal A activity, kidney biopsy, genetic studies, and lyso-Gb3 levels as diagnostic tools. A total of 24% of nephrologists did not agree with the need for a Fabry nephropathy registry. Most experts agreed with measuring lyso-Gb3 as a biomarker. Currently, measurements of lyso-Gb3 are not covered by insurance, so it is being requested by a specific company. If lyso-Gb3 is covered by Korean health insurance, most specialists reported that they would measure lyso-Gb3 after ERT treatment. However, most non-nephrologists agreed that measuring lyso-Gb3 after treatment would be appropriate but would perform such measurements at the time of diagnosis. New biomarkers such as lyso-Gb3 were impaired in patients with normal albuminuria levels [

12,

17,

25] and were more closely correlated with the expression of Fabry nephropathy [

18]. Unpublished data from a Korean study by Cho et al. found that lyso-Gb3 is a screening marker that can identify patients who are eligible for a Fabry gene analysis in patients with chronic kidney disease with unknown etiology. This suggests that coverage by insurance should be considered.

Half of the respondents (54.4%), particularly nephrologists, selected proteinuria and eGFR by serum creatinine to measure kidney function every 3 months. Although proteinuria and GFR are considered important markers of Fabry nephropathy, most kidney involvement occurs in a non-proteinuria state [

2,

3,

26]. These findings suggest that the field of expertise of the treating physicians should be given greater attention. Nephrologists evaluate kidney involvement using a kidney biopsy earlier than do non-nephrologists [

24,

26]. In addition, they treat and monitor kidney involvement more proactively than do non-nephrologists. Consequently, for the treatment of Fabry disease, a discussion with a specialist in the relevant field will be of great benefit.

This is the first survey of Korean experts on Fabry disease and how they manage Fabry nephropathy. Unlike previous Korean patients with Fabry disease studied by a nationwide survey, most patients being treated by survey respondents had a variant form of the disease [

16]. The specialty of the diagnosing physician influenced the phenotype of the disease in each patient. Nephrologists and cardiologists treat more patients with variant types, while pediatricians see those with the classic type (

Fig. 1). Recent screening studies of Fabry disease in high-risk clinics (1995ŌĆō2017) confirmed this pattern [

23]. Two Korean patients with Fabry nephropathy reportedly progressed to kidney failure with renal replacement therapy in 1989. Recently, a cardiac variant was reported in Korea [

27]. Because Korean experience with Fabry disease has been sporadic and intermittent until recently, clinicians are interested in sharing their experiences with the disease [

28]. A recent unpooled systematic review found that different patient populations could require different disease-management and therapeutic goals depending on age, genotype, and disease severity and/or level of organ involvement [

13]. Although National Health Insurance service benefits set by the KCD (during the 3 months after registration) was 38,903,000/person, the burden of cost remains a barrier for ERT in Fabry disease, particularly for female patients with classic Fabry disease or other patients with the variant type. Fewer reports of ERT in adult females were available compared with those in adult males due to the limitations of retrospective observational and case-series studies [

13]. Clinicians, and nephrologists in particular, prefer to monitor kidney manifestations to determine the timing of ERT after diagnosis. Most respondents chose microalbuminuria as the appropriate stage to initiate ERT. An angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and/or angiotensin receptor blocker was considered a non-ERT treatment, followed by a low-protein diet and low sodium intake.

Diagnostic and treatment guidelines for Fabry disease emphasize a multidisciplinary approach to disease management due to multisystem involvement [

14,

29]. Our findings show that specialists in the field of nephrology have limited expertise with tests and medicines. In fact, a survey of nephrologists in France revealed that knowledge of kidney injury was poor (less than 50% chose the correct answers in a test) [

21]. In addition, nephrologists may lack the experience of other specialties when it comes to phenotype or genetic testing; therefore, patients with Fabry disease should receive care from a multidisciplinary team comprising experienced professionals in neurology, cardiology, pediatrics, and genetics, in addition to nephrology.

This research had numerous limitations. First, selection and recall bias is possible in a voluntary survey questionnaire. Second, due to the limited number of specialists with experience in treating this disease, only a small number of respondents completed the survey. Third, responders may have been confused about phenotypic categories because classic and variant phenotypes were not defined in this survey. Fourth, pediatric nephrologists may be considered non-nephrologists due to the nature of their sub-specialty training. Finally, clinicians may diagnose or treat Fabry nephropathy based on the Korean medical insurance indications.

The majority of respondents to the survey were medical professionals who have treated or are currently treating a patient with Fabry disease. They agreed that it is important to initiate ERT early in Fabry nephropathy, particularly in patients with the variant type of the disease, and that lyso-Gb3 is a valuable biomarker, highlighting the importance of insurance coverage for lyso-Gb3 testing.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement table 1

Supplement table 1 Print

Print