| Kidney Res Clin Pract > Volume 39(4); 2020 > Article |

|

Botropase is a snake venom-based hemocoagulase with thrombin-like activity [1]. Despite its clinical use over several decades, its therapeutic effect has been controversial, and no study about botropase effect on platelet function has been reported. In this report, we present two cases with markedly decreased platelet function after receiving intravenous botropase, especially one of whom, with end stage renal disease (ESRD), showed a severe bleeding complication. On April 20, 2020, a 59-year-old man (case 1) visited our hospital for spinal stenosis surgery. His past medical history was pertinent, with diabetes diagnosed at the age of 40 and hemodialysis since February 2017. He did not take any antiplatelet medications for several months before the surgery. Initial laboratory findings showed white blood cell count 8.8 × 103/µL, hemoglobin 10.0 g/dL, hematocrit 29%, platelet count 162 × 103/µL, blood urea nitrogen 45 mg/dL, creatinine 6.3 mg/dL, glucose 92 mg/dL, prothrombin time 13.4 seconds, protein C activity 97%, protein S activity 78%, von Willebrand factor 150%, antithrombin III 80%, and fibrinogen 116 mg/dL.

After surgery, the surgeon prescribed a hemocoagulase based on the medication instruction from the manufacturer (Hanlim Pharm Co., Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea); one ample of botropase (each ample contains 2 IU/2 mL) mixed with 100 ml of normal saline, administered intravenously for 30 minutes, twice a day for three days.

The patient began to complain of epigastric fullness and soreness after surgery. On day six of hospitalization, esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed, and acute gastric ulcer with active bleeding was detected on the antrum. Endoscopic hemostatic clip application was performed successfully. Botropase (4 mL/day) administration was reinitiated from hospitalization days 6 to 11. On days eight and 11 of hospitalization, desmopressin acetate (six amples of 4 µg each) with 400 mL of a cryoprecipitate was prescribed to control uremic bleeding [2]. However, hematochezia continued, and anemia was not corrected despite blood transfusion, suggesting hidden lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Both adenosine diphosphate (ADP) stimulation and arachidonic acid-trigger platelet aggregation were assessed in whole blood specimens with a commercial assay kit, using a multiple electrode impedance platelet aggregometer (The Multiplate; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) [3]. Ultimately, the results of either test predict the degree of inhibition of GpIIb/IIIa [4] on the platelet surface. The overall platelet activity was presented as area under the aggregation curve (AUC). Expected values of AUC units (U) (reference range of a normal person), i.e., 71.0 to 115.0 AUC U for arachidonic acid trigger test and 57.0 to 113.0 AUC U for ADP stimulating test, have been established in a manufacturer study with healthy donors [5,6].

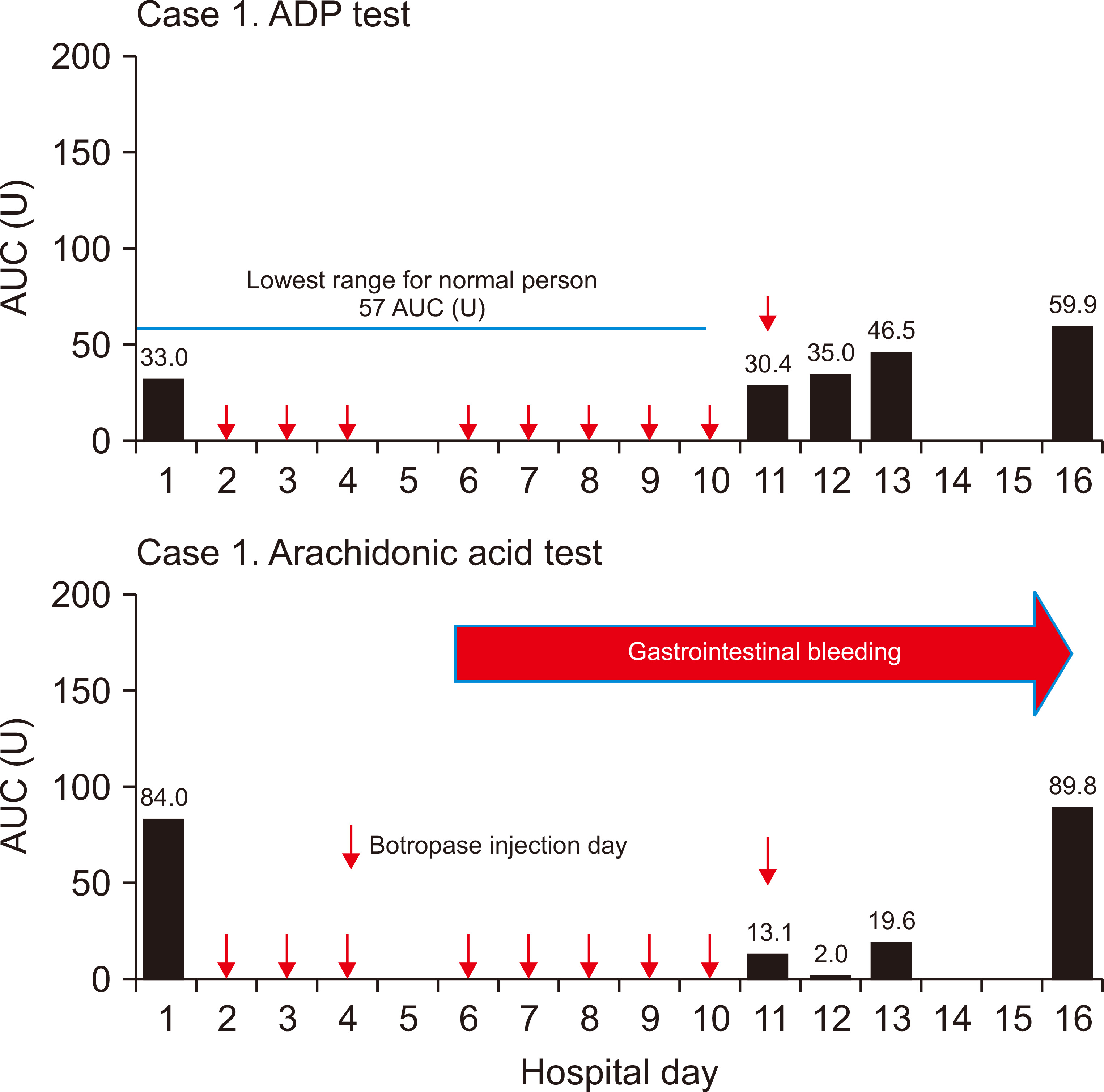

The platelet function tests were performed on hospitalization days one (pre-botropase injection), 11, 12, 13, and 16. The results were 84.0, 13.1, 2.0, 19.6, and 89.8 AUC U for arachidonic acid trigger test and 33.0, 30.4, 35.0, 46.5, and 59.9 AUC U for ADP stimulating test, respectively (Fig. 1).

In light of the unexpected deterioration of platelet function, we discontinued botropase treatment immediately. Complete cessation of bleeding was confirmed using a negative stool occult blood test on day 26 of hospitalization.

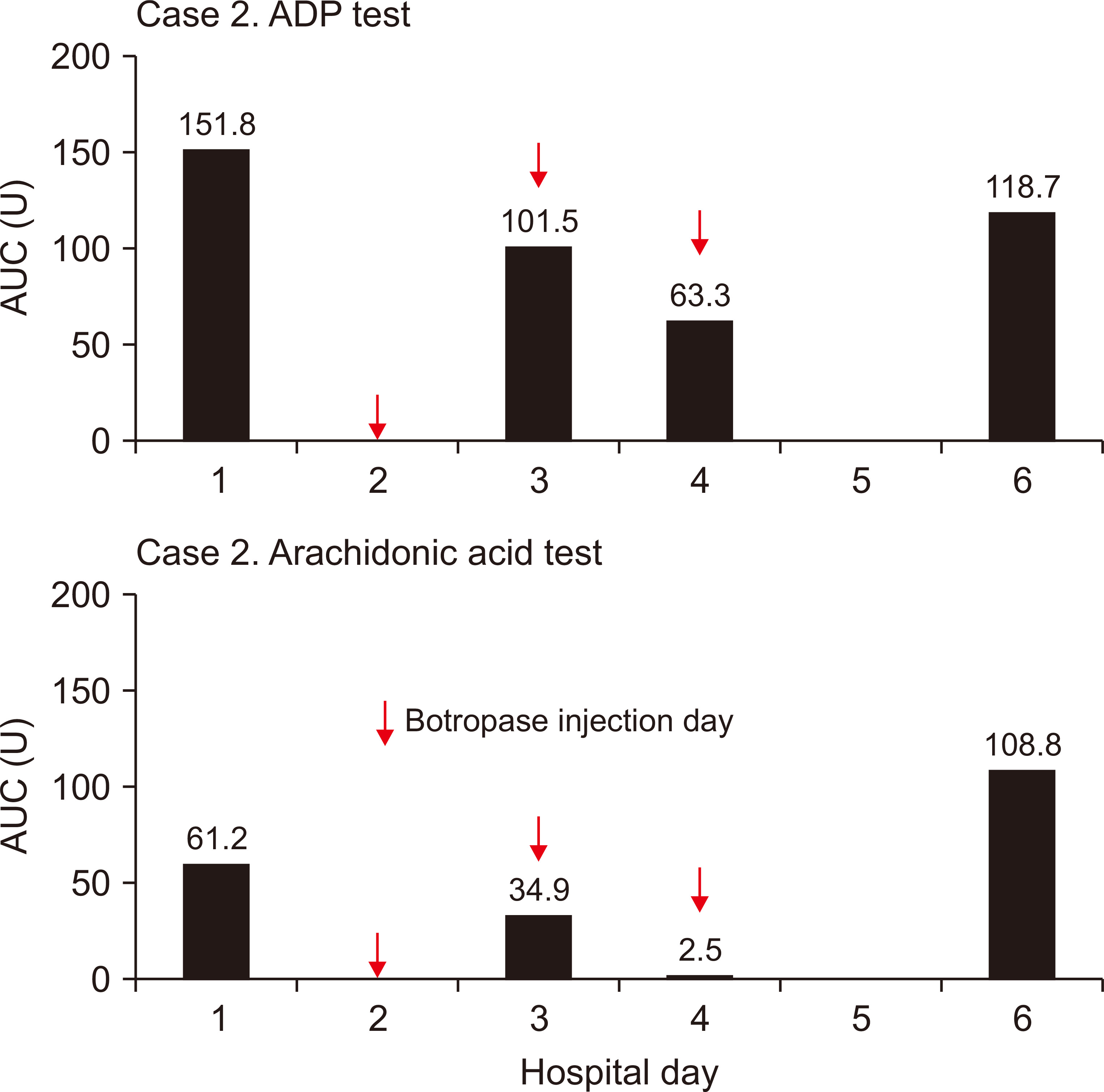

On April 21, 2020, a 77-year-old man (case 2) visited our hospital for spinal stenosis surgery. The kidney function was normal. The surgeon prescribed botropase (4 mL/day) for three days after the surgery, as usual. The results of platelet function, measured at pre-botropase injection, second, and third day post-botropase injection, as well as two days after discontinuing botropase treatment were 61.2, 34.9, 2.5, and 108.8 AUC U for arachidonic acid trigger test and 151.8, 101.5, 63.3, and 118.7 AUC U for ADP stimulating test, respectively (Fig. 2). There were no bleeding-related complications in case 2.

In general, the etiology of bleeding in the ESRD patient was due to so called “uremic bleeding” of which the main pathophysiology is platelet dysfunction [7,8]. However, great disparity was observed in the results of arachidonic acid trigger test between pre- and post- (lowest) botropase administration in the ESRD patient (84.0 vs. 2.0 AUC U) (Fig. 1).

To observe whether the same result can be found in a patient with normal renal function, we measured platelet function in a patient with normal renal function, before and after botropase administration. The result was 61.2 and 2.5 AUC U for arachidonic acid trigger test and 151.8 and 63.3 AUC U for ADP stimulating test, respectively (Fig. 2). However, this dramatic change was not observed via the ADP stimulating test in the ESRD patient because the basal level (33.0 AUC U) was far below the reference level (57.0 to 113.0 AUC U) (Fig. 1).

In summary, despite the thrombin-like activity of botropase on fibrinogen, the adverse effect of botropase on platelet function seems to offset its hemocoagulation effect, regardless of kidney function. Clinicians, particularly clinical nephrologists, should be mindful about the antiplatelet effect of botropase when it is used as a hemocoagulase.

Acknowledgments

Professor Samel Park (Department of Nephrology, Sooncheonhyang University Cheonan Hospital, Cheonan, Korea) helped us edit this manuscript.

Notes

Authors’ contributions

Byung Soo Kang and Seong Su Ban provided intellectual content of critical importance to the work. Won Seon Han and Byung Geun Kim participated in technical support and coordination. Young Il Kim participated in the conception and interpretation of data. Sae-Yong Hong participated in writing, original draft preparation, reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Figure 1

Sequential measurements of the platelet aggregation function test in case 1.

Botropase is initiated on two separate occasions. First, botropase 4 mL/day for three days after the surgery as usual. No platelet function test was performed during this period. Second, botropase initiated between hospitalization days 6 and 11 to treat gastric ulcer bleeding. The platelet function test was performed four times on hospitalization days 11, 12, 13, and 16.

ADP, adenosine diphosphate; AUC, area under the aggregation curve; U, units.

Figure 2

Sequential measurements of the platelet aggregation function test in case 2.

The platelet function test was performed on hospitalization days 1, 3, 4, and 6. Botropase-mediated platelet dysfunction developed within three days after injection and recovered within two days after cessation.

ADP, adenosine diphosphate; AUC, area under the aggregation curve; U, units.

References

1. Shenoy AK, Ramesh KV, Chowta MN, Adhikari PM, Rathnakar UP. 2014;Effects of botropase on clotting factors in healthy human volunteers. Perspect Clin Res 5:71–74.

2. Galbusera M, Remuzzi G, Boccardo P. 2009;Treatment of bleeding in dialysis patients. Semin Dial 22:279–286.

3. Paniccia R, Priora R, Liotta AA, Abbate R. 2015;Platelet function tests: a comparative review. Vasc Health Risk Manag 11:133–148.

4. Vickers JD. 1999;Binding of polymerizing fibrin to integrin alpha(IIb)beta(3) on chymotrypsin-treated rabbit platelets decreases phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and increases cytoskeletal actin. Platelets 10:228–237.

5. Sibbing D, Braun S, Morath T, et al. 2009;Platelet reactivity after clopidogrel treatment assessed with point-of-care analysis and early drug-eluting stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 53:849–856.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles

-

Isolated Pancreatic Tuberculosis in a Patient with End-Stage Renal Disease2011 September;30(5)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print